Trustees of the De Morgan Basis

Trustees of the De Morgan BasisEsoteric and pioneering, the work of a lesser-known Pre-Raphaelite, Evelyn De Morgan, explored the trauma and that means of battle – and prefigured present fantasy artwork.

On a rocky seaside that glows purple with lava, smoke-breathing dragons encompass wretched-looking prisoners beseeching an angel to ship them from struggling. The oil portray Dying of the Dragon by Evelyn De Morgan seems at first like a scene from the New Testomony’s apocalyptic E book of Revelation. However, painted between 1914 and 1918, it is also one thing extra private and important: an allegory for the distress and bondage of World Warfare One, and the confrontation between good and evil.

Trustees of the De Morgan Basis

Trustees of the De Morgan BasisThe present coincides with the reopening of the De Morgan Museum in Barnsley, Yorkshire, following an in depth roof renovation, and responds to a rising curiosity on this lesser-known artist. She has tended to be eclipsed by her husband William – a ceramicist and author, who had labored early in his profession with the textile designer William Morris – and the well-known males of their circle: her uncle and artwork instructor, John Roddam Spencer Stanhope, for instance, and the painters William Holman Hunt and Dante Gabriel Rossetti. A lot of what we learn about De Morgan in the present day comes from her sister Wilhelmina, who arrange the De Morgan Basis, however even she noticed match to publish the couple’s posthumous biography underneath the title William De Morgan and his Spouse.

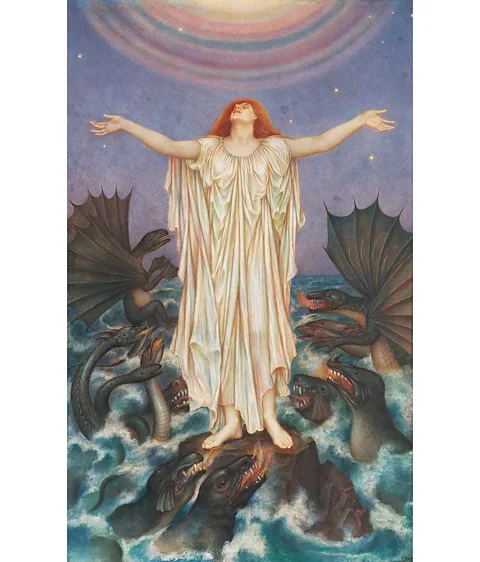

But, Evelyn De Morgan greater than deserves the artwork world’s belated acclaim. A Slade graduate, who was working on the tail finish of the Pre-Raphaelite motion, she took the arguably twee or overly sentimental style into new territory, creating tableaux that have been unusually visionary and energetic. The ladies she portrayed have been much less passive than these depicted by her contemporaries, and featured as symbols of company moderately than objects of the male gaze. As a substitute of a drowned physique floating down the river, as in Sir John Everett Millais’ Ophelia, or figures whose essential foreign money was their seems, we meet a talented sorceress creating magical potions and flying superheroines who can forged rain, thunder and lightning from their fingers.

These goddess-like figures present the affect of the classical artwork that De Morgan had studied. Immaculately executed works akin to Boreas and Oreithyia (1896) reveal her curiosity in mythology and her mastery of the human kind, harking back to Michelangelo.

In Dying of the Dragon, when it comes to composition, it is simple to see the affect of Sandro Botticelli’s The Beginning of Venus (1483–1485), which De Morgan had visited in Florence. If De Morgan’s haloed angel echoes this concept of rebirth − reflecting the artist’s perception in a non secular afterlife − then the winged beasts are its counterpart, Dying, at all times biting on the heels of the folks and threatening to beat them. Elsewhere in her work, Dying takes different kinds: a darkish angel bearing a scythe, sea monsters or – extra obliquely – a sand timer. It is a symbolism that speaks to life’s transience, and acquires further poignancy in her later work, conveying the collective trauma of dwelling by means of a World Warfare that claimed near 1,000,000 British lives.

Trustees of the De Morgan Basis

Trustees of the De Morgan Basis“Through the First World Warfare they [the De Morgans] have been in London, so they’d have been straight affected,” Jean McMeakin, Chair of the Board of Trustees of the De Morgan Basis, tells the BBC. “Dying was actual for them in a means that maybe we have largely forgotten today,” she factors out. “Members of William’s household died from tuberculosis, and his personal well being was usually fairly poor. Dying was, in a means, at all times current within the background.”

De Morgan was a pacifist and her artwork turned a type of activism. In Our Girl of Peace (1907), a response to the Boer Wars, a knight pleads for cover and peace, whereas in The Poor Man who Saved the Metropolis (1901), knowledge and diplomacy are advocated as options to navy intervention. Later, in The Crimson Cross (1914-16), angels carry the crucified Christ over a withered panorama pierced by Belgian battle graves – a suggestion, maybe, that the Christian religion is at odds with the brutality of battle, however affords us hope of redemption. “You have to by no means reward battle,” De Morgan declared in The Results of an Experiment (1909), a guide of “automated writing” co-authored together with her husband. “The Satan invented it, and you’ll don’t have any conception of its horrors.”

Good and evil

The concept of the forces of excellent and evil performing upon extraordinary folks was pervasive right now. “Spiritualism was fairly common,” asserts McMeakin, citing the writer Sir Arthur Conan Doyle – the creator of Sherlock Holmes – as one in all its most well-known adherents. Different-worldly beliefs, she says, have been “in all probability the results of the turmoil, the huge modifications taking place in society main as much as the flip of the century, plus a interval of many wars, which might have had an impression on their view of the world”. Likely, De Morgan was additionally influenced by her mother-in-law, Sophia, a widely known spiritualist and medium. With so many lives misplaced, it was little question tempting to imagine that you can reconnect with the departed.

Trustees of the De Morgan Basis

Trustees of the De Morgan BasisFor De Morgan, materialism was in opposition to spirituality, and plenty of of her works conflate the pursuit of wealth with loss of life. Crowns, as worn by the winged serpents in Dying of the Dragon, are a repeated motif denoting greed and miserliness. In Earthbound (1897), an avaricious king in a gold cloak patterned with cash is about to be overwhelmed by the angel of loss of life, whereas in The Barred Gate (c.1910-1914), an identical determine is denied entry to Heaven.

With the long run so unsure, De Morgan locations the significance of non secular fulfilment and happiness on the centre of a lot of her work. In Blindness and Cupidity Chasing Pleasure from the Metropolis (1897), for instance, “Cupidity” is personified as a topped determine clutching treasures who’s driving away “Pleasure” within the type of an angel. Right here, as in Dying of the Dragon, the central characters are chained, suggesting trapped souls.

In The Prisoner (1907-1908), the barred window and a lady’s chained wrists make captivity a metaphor for gender inequality, hinting on the De Morgans’ assist for common suffrage (Evelyn was a signatory of a minimum of two necessary petitions, whereas her husband was vice-president of the Males’s League for Girls’s Suffrage). The theme recurs in Luna (1885), the place the rope-bound physique of a moon goddess, a mythological determine of female energy, features as a metaphor for a girl’s wrestle to affect her personal future.

Trustees of the De Morgan Basis

Trustees of the De Morgan BasisChristened “Mary”, Evelyn later adopted her then-gender-neutral center title, as girls’s artwork was not taken significantly. “She needed to be thought of on the identical stage as her male friends,” says McMeakin. “We are able to assume an enormous diploma of self-possession and dedication in her want to change into an expert artist,” she provides, making the purpose that even De Morgan’s mom opposed her profession selection.

Technically, De Morgan was additionally a pioneer. She experimented with burnishing and rubbing gold pigment into her works so as to add depth and curiosity, and explored new portray methods invented by her husband, made by grinding colors with glycerine and spirit. Stylistically, she was additionally forward of her time. The unconventional use of pinks and purples, and the daring rings of rainbow-coloured mild, prefigure the psychedelic portray kinds of the Seventies, whereas her terrifying monsters wouldn’t look misplaced in up to date fantasy artwork.

Whereas artwork historical past has tended to color girls as virgin moms, objects of magnificence or temptresses, De Morgan’s particularly feminine perspective recasts them as figures of hope that augur another, brighter future. In Lux in Tenebris (mild in darkness) (1895), for instance, the feminine determine holds an olive department in her proper hand, providing a pathway to peace. In Dying of the Dragon, the angel is surrounded by a powerful rainbow: an emblem (together with the sky) of pleasure that denotes non secular fulfilment and freedom, in addition to the promise of an afterlife.

Trustees of the De Morgan Basis

Trustees of the De Morgan BasisIt is a mistake to think about works akin to Dying of the Dragon as “fully bleak”, argues McMeakin, noting that “usually with [her] apocalyptic scenes, there’s a glimmer of hope, or part of the portray that’s calm”. In some ways, Dying of the Dragon is optimistic, expressing a way that the battle – the metaphorical dragon – is nearing its finish, and that good can overcome evil. On this existential battle, De Morgan noticed a spot for her work. When she was aged simply 17, she chastised herself for not portray sufficient. “Artwork is everlasting, however life is brief,” she wrote in her diary. “I’ll make up for it now, I’ve not a second to lose.”