The next textual content is a chapter from Decolonising Artwork: Past the Apparent (2025), a publication that summarizes and paperwork a public programme of the identical title from the Ukrainian Pavilion on the 59th Worldwide Artwork Exhibition of the Venice Biennale.

academia will speak about decolonization

it is going to speak about it on a regular basis

however aside from the few

it is not going to speak about your father, brothers, sisters, pals

these in chilly trenches, decolonizing by way of de-occupation

that won’t be epistemic sufficient to be mentioned

Darya Tsymbaliuk, DO NOT DESPAIR. a letter to a scholar whose homeland shall be attacked by Russia subsequent

I’m scripting this in March 2024, two years after the beginning of the full-scale Russian invasion of Ukraine and a 12 months and a half after I used to be invited to talk as a part of the Ukrainian Pavilion on the Venice Biennale, which this 12 months opens in mid-April. Proper now, Andrii Dostliev and I are ending a mission which was commissioned for it, ‘Consolation Work’.

Regardless of the horrors of the struggle, 2022 additionally introduced hope: hope that, by making a consolidated effort and partnering with like minded allies Ukrainian cultural professionals may be capable of shift, make clear and finally undermine the privilege and centrality of Russian tradition.

As my colleagues and I’ve written in earlier articles, the start of the struggle in February 2022 marked a turning level as Ukraine shifted from a post-colonial state to a decolonial one. Conversations in Venice have been stuffed with optimistic expectations of change, and most of the contributors, I feel, envisioned themselves as an energetic a part of it.

I keep in mind the second at first of the struggle once I realized that the rationale why Ukrainian cultural illustration on the earth is so weak – right here and elsewhere I take advantage of the phrase ‘Ukrainian’ in its civic and political, not ethnic dimension – is above all the shortage of accessible platforms for public expression. The truth, nevertheless, turned out to be way more advanced.

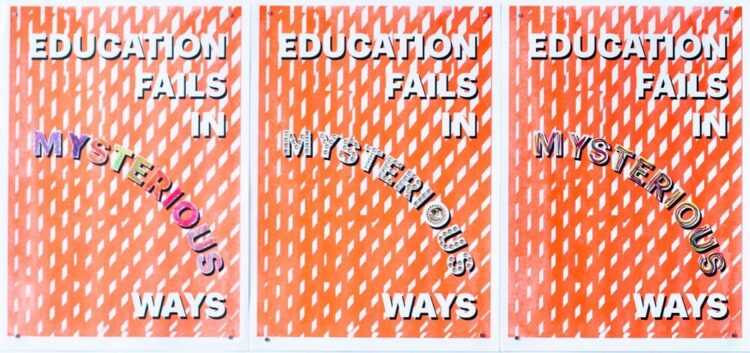

Andrii Dostliev, ‘Training fails in mysterious methods’, riso-type posters, 2023. Picture courtesy of artist

As Didier Fassin and Richard Rechtman write of their e book The Empire of Trauma, the earthquake which levelled a number of Armenian cities in 1988, leaving tens of 1000’s useless and over 100 thousand wounded, additionally turned a politically important occasion as a result of ‘in sensible phrases, it gave the West its first alternative to enter this area.’ Fassin and Rechtman attribute this to the truth that the Soviet world ‘had hitherto been firmly closed to all outdoors interference.’ Nevertheless, over thirty years after the collapse of the USSR, residents of territories that have been as soon as pressured to be a part of it have repeatedly discovered that the eye of the West is extraordinarily selective and never essentially depending on how open a rustic’s area is. A pure catastrophe or a struggle at house could certainly draw consideration to the affected area for a short while – with international media shops protecting occasions as in the event that they’ve simply found your a part of the world on the map. In 2014, when Russia occupied Crimea and components of Donetsk and Luhansk areas, after which when the full-scale invasion started eight years later, the so-called collective West observed Ukraine as if for the primary time, considerably stunned to comprehend that between Berlin (or, in case you are very fortunate, Warsaw) and Moscow lies not an infinite and anonymous wilderness however a territory with residing individuals who have their very own language and tradition however whose properties are being destroyed as I write.

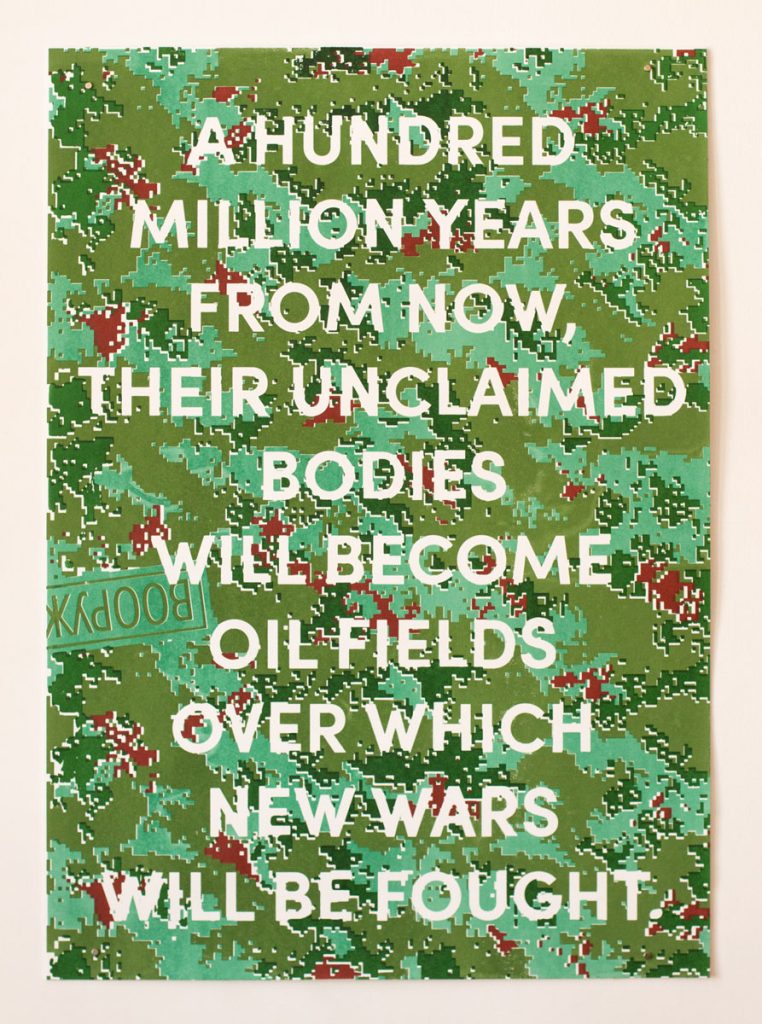

Andrii Dostliev, ‘Useless Pixels’, silkscreen poster, 2022. Picture courtesy of artist

The consequence of your nation being part of traumatic geography on the Western psychological map is a really particular type of consideration and recognition that your society receives. The Oscar awarded to the movie 20 Days in Mariupol by Mstyslav Chernov is a vivid instance: it’s exhausting to think about a Western director beginning their speech with the phrases ‘I want this movie had by no means been made.’

The wave of curiosity in Ukrainian tradition provoked by the full-scale invasion has undoubtedly led to the creation of recent public platforms and alternatives to manifest Ukraine’s cultural presence. Nevertheless, this consideration has been given on reasonably inflexible phrases. It wasn’t due to a sudden realization that the big selection of cultural kinds that exist inside Ukraine are not any much less useful than these of Russia or the West. This scrutiny comes with an embedded hierarchy and is a type of non permanent solidarity with a group that’s being bodily destroyed by a stronger pressure. The cultural worth of the product that was given public publicity – significantly at first of the full-scale invasion – was subsequently a secondary concern. The principal one was that its creators have been from Ukraine and could possibly be supplied with cultural humanitarian support.

Consequently, we witnessed a surge in Ukraine-related occasions overseas which have been usually of poor inventive high quality. They have been organized by establishments that needed to assist however usually lacked each the experience to create a high quality product and the flexibility to comprehend their shortfall. Exhibitions devoted to Ukraine featured artists whose Ukrainian origin was the one factor they’d in frequent, lacking any clear curatorial message.

The flooding of those occasions into the cultural area blurred the boundaries between emergency residencies or exhibitions organized as a gesture of solidarity {and professional}, quality-based Ukrainian tasks. Furthermore, the non permanent hype led cultural staff, a few of whom had constructed their whole careers overseas, to be perceived as mere Ukrainian our bodies, no matter their skilled stage. They have been seen as bearers of trauma and their actions framed completely in identity-based classes.

The obvious demand for high quality Ukrainian artwork which ‘can do greater than communicate of struggle and act as a perpetual reminder of the urgency of the scenario’ versus artwork which fails to ‘override fastened and binary classes of identification’ excludes a number of crucial issues. Firstly, Ukrainian artwork which is anticipated to be ‘greater than nationwide’ and strikes past ethnic dimension is framed in synthetic classes of nationwide identification primarily by critics’ descriptions, curators’ work, and the viewers’s notion, which is a symptom of taking a look at Ukraine by way of the lens of colonial Russia (or, as within the case of Poland, conditioned by its personal colonial previous too). It’s inconceivable to make ‘post-national’ artwork if those that take a look at it and people who describe it nonetheless understand the work when it comes to the writer’s nationality and see its ‘Ukrainianness’ as its predominant attribute.

One other downside with offering public platforms to characterize Ukrainian tradition within the West is that such platforms usually create a ‘ghetto’ of kinds, the place solely Ukrainians (refugees or diaspora) and some like-minded allies attend occasions devoted to Ukraine. This format maintains the present colonial hierarchy: it signifies solidarity however lacks any emancipatory potential as a result of it doesn’t contain integration with a broader viewers past the slim pool of Ukrainian sympathizers, nor does it present the potential for actual affect. The audience for decolonial change merely don’t come, and a Ukrainian bubble subsequently arises, the place an area is formally supplied for the illustration of the ‘emotional and traumatized Ukrainian voice’, however that voice just isn’t heard.

To the west of the Oder river, this smattering of charitable deeds was additionally a way of redemption: it’s simpler to supply Ukrainian artists with area in an establishment for a one-day occasion between deliberate exhibitions than to ponder how a long time, even centuries of deal with the tradition of a neighbouring colonizer and the adoption of its gaze as default contributed to the normalization of Russia’s wars and the 2022 invasion of Ukraine. The proliferation of Ukraine-related decolonial occasions paradoxically serves as an alternative to actual decolonial (learn: structural) adjustments.

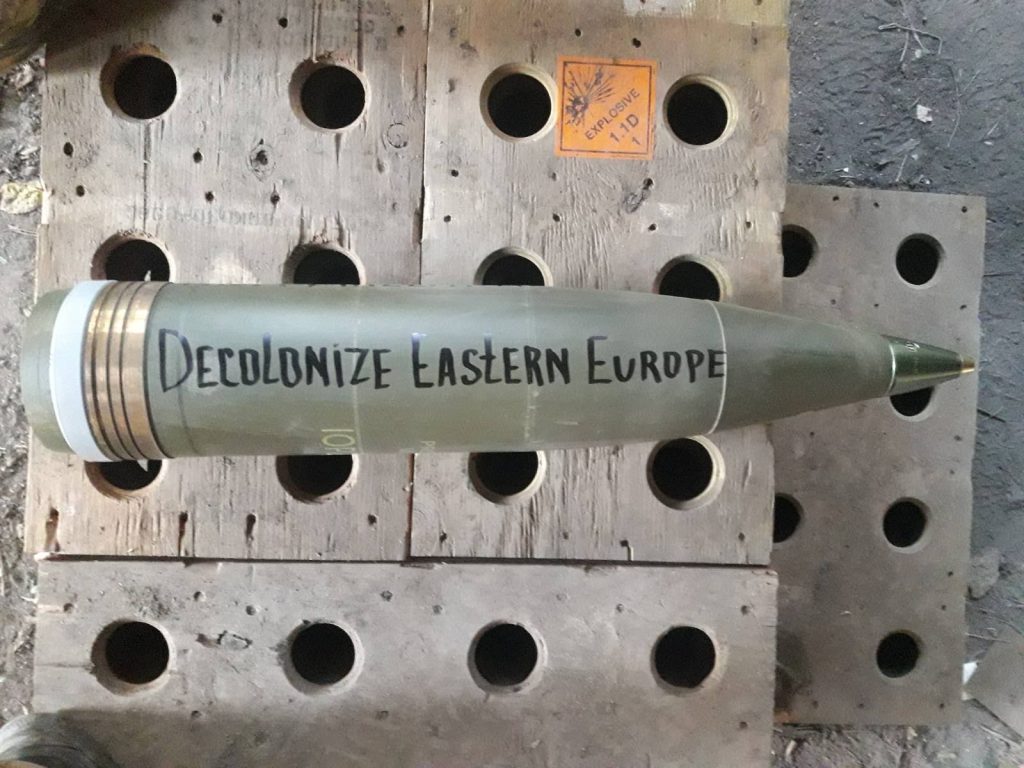

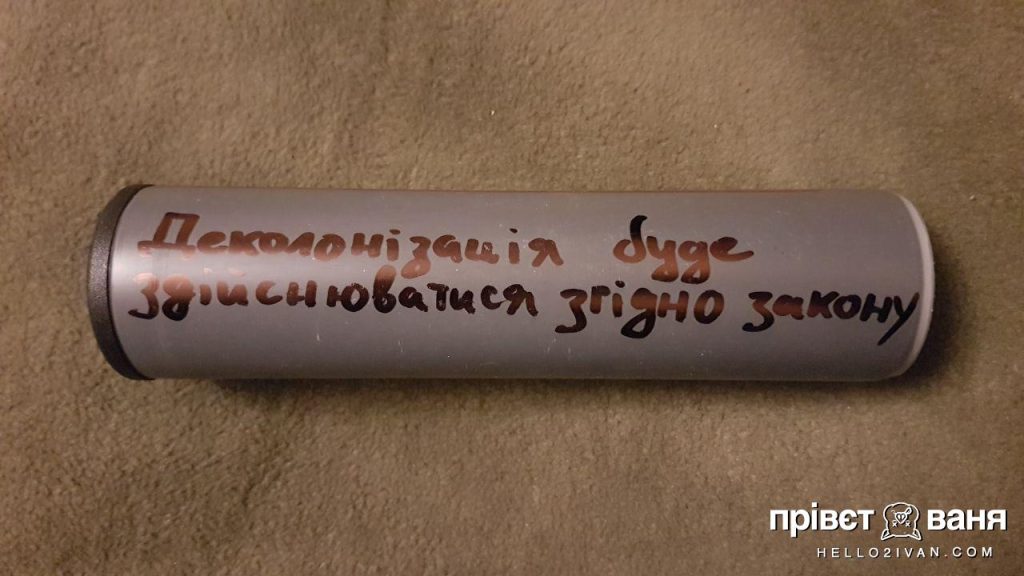

Andrii Dostliev, from ‘It’s decolonial‘ sequence, 2023. Pictures courtesy of artist

For the reason that starting of the full-scale invasion, I’ve repeatedly discovered myself in conditions the place breaking the sample of making a ‘Ukrainian ghetto’ and the attendance of non-Ukrainians at Ukrainian occasions turned a supply of tension for Western hosts: ‘Who’re these individuals within the viewers? Are you aware them? Are they your folks?’

Now, two years on, it may be argued that what we initially perceived as a shift in the direction of decolonization was only a non permanent Ukrainian quota with little potential for structural change. Quite the opposite, establishments – each in tradition and academia – have mobilized current sources to protect their establishment, making ready to contest even the potential risk to their place of privilege.

Varied methods of appropriating the decolonial discourse and instrumentalizing it to protect the prevailing colonial hierarchy could be cited right here as examples. Marking the time period ‘Russian tradition’ as problematic has led many cultural figures who had constructed their skilled identification in affiliation with it to unsubscribe from the symbolic area. Instantly, everybody stopped being Russian, however continued to defend their skilled proper to talk on behalf of the complete area of the previous Russian colonies. Individuals who left Russia after 2022, having already constructed their careers there, instantly stopped utilizing the phrase ‘Russia’ of their bios and/or have found some family members – at all times feminine: grandmothers or aunts, for some cause – in Ukraine or different former colonies, the place they spent quite a lot of time as kids, having fun with tasty nationwide meals and the nice sounds of a considerably humorous native language. Symbolically leaving the set of these focused by the decision to ‘decolonize Russian tradition’, all these people started to think about themselves a part of a group that shall be now answerable for ‘decolonisation’ – or reasonably, the preservation of the prevailing colonial hierarchy, however this time in a decolonial wrapper. Western establishments supported this relabelling, readily offering an area for self-proclaimed ex-Russians to characterize everything of a area which was as soon as Russia’s empire.

Photographs from the efficiency ‘Grandma from Zhytomyr’, Schinkel Pavilion, Berlin, 2024. Picture courtesy of artist

The sudden search in a single’s household ancestry for extra oppressed heritage has nothing to do with precise decolonization by way of addressing colonial erasure or bringing again plurality. It’s, in reality, the other of in search of decolonial justice: so long as the identification of a Russian curator – or another public determine – offers privileged entry to institutional sources, everyone seems to be happy. One other problematic facet of such shifts in identification is the understanding of 1’s connection to the Ukrainian context when it comes to ‘primitive ultranationalism’ – actually by way of blood and soil, which ignores the civic, social and political dimensions. From this angle, belonging to a sure cultural group is one thing one is born into; it has nothing to do with acutely aware selection or the performative, on a regular basis element of that tradition, which is itself lowered to ethnic kitsch. We subsequently have a peculiar paradox: the reappropriation of the colonized identification and the simultaneous preservation of the colonial gaze on this identification. (It’s price mentioning that Western researchers historically attribute ‘dangerous nationalism’ – monoethnic, monocultural, aggressive in the direction of something that isn’t its constituent – to previously colonized nations that gained statehood.)

What ought to we then do? If Ukraine desires to maintain alive the dialogue about decolonial approaches – and I hope it does – we must always focus, at the start, on creating new horizontal connections with representatives of different former colonized communities which have comparable experiences of oppression. It’s with them that, for my part, the Ukrainian cultural group ought to primarily have interaction and unite.

This essay was first revealed in Decolonising Artwork: Past the Apparent. Study extra in regards to the publication right here.