Property of Corinne Day/ Bridgeman Pictures

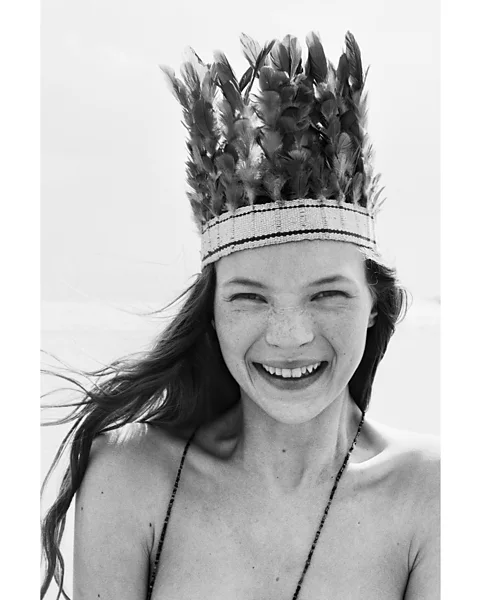

Property of Corinne Day/ Bridgeman PicturesAn iconic picture of Kate Moss marked an explosive second of change in Britain – and helped to create the tradition we now reside in. It is among the many images displayed in a brand new exhibition that celebrates the pictures of The Face journal.

Freckled and fresh-faced, a 16-year-old Kate Moss laughs, make-up-free and unadorned apart from a fragile string of beads and a headdress fabricated from feathers – the picture on the duvet of The Face journal in July 1990 was completely timed. It captured a second in Britain when the nation’s youth was coalescing round a burgeoning acid-house motion, with impromptu events filling disused warehouses, plane hangars and fields throughout the nation. The escapist, chaotic rave scene that spanned class and race was an explosion of optimism and euphoria amid tough instances of excessive unemployment and a weak economic system. The journal’s cowl portrait marked a brand new period, with Kate Moss the approaching decade’s feather-crowned queen.

The long-lasting portrait by Corinne Day is among the many images on show at London’s Nationwide Portrait Gallery within the exhibition The Face Journal: Tradition Shift. Lee Swillingham, former artwork director of The Face – together with photographer Norbert Schoerner – got here up with the thought for the present, which charts the British fashion journal’s pictures by means of the years. “For me, The Face actually was the very best chronicler of British youth tradition,” says Swillingham, who co-curated the exhibition with NPG’s senior curator of images, Sabina Jaskot-Gill.

The Moss portrait was “a breath of recent air,” Swillingham tells the BBC. “It was a second of shifting on from the aspirational, stylised glamour of the 80s, and right into a extra pared-down and practical part in trend phrases. That entire pictures fashion went hand in hand with a extra attainable sense of magnificence.”

Property of Corinne Day/ Bridgeman Pictures

Property of Corinne Day/ Bridgeman PicturesIt was Swillingham’s predecessor as artwork director Phil Bicker who initially championed the rising photographer Corinne Day and the then unknown teenage mannequin Kate Moss. “I used to be looking for somebody who could be ‘the face of The Face’,” Bicker tells the BBC – not a shiny, “aspirational” trend muse however a pure, actual one, in tune with the journal’s readership. “Kate had the Britishness and youthfulness that The Face represented – she was humorous, and laughed lots. She appeared to me an individual first, and a mannequin second.” Contained in the July 1990 difficulty of the journal, Moss is proven on the seashore at Camber Sands on the south coast of England, messing about guilelessly in a sequence of images putting of their simplicity and naturalness.

It was “an ideal storm,” says Bicker. “And regardless of Kate’s subsequent world profile and in depth profession, she’s nonetheless related to The Face, and that defining second which launched her profession. It was shot in a approach by Corinne that allowed Kate’s persona and optimistic vitality to come back by means of, in order that when individuals noticed the pictures, they forgot they had been taking a look at a styled trend story, as an alternative believing this was a portrait of Kate unadorned.”

Moss nor her company notably appreciated this uncooked, barely gawkish depiction of the mannequin, in line with Sheryl Garratt, then The Face editor, writing in The Observer in 2000. The shoot has nonetheless remained a cultural touchstone, embodying a second in time. The journal’s founder Nick Logan later mentioned: “At the moment, at the beginning of the rave scene, I keep in mind saying, ‘let’s intention it at these individuals dancing in fields’.” The 1990 photographs of Moss mirrored not solely a brand new aesthetic but in addition a deeper cultural change within the UK, with the duvet line of the journal referring to a “summer season of affection”, in reference to the exploding out of doors rave scene.

“It was an actual second of transition,” Angela McRobbie, professor of cultural research at Goldsmiths, College of London, tells the BBC. “It marked a shift, when a subculture moved into mass visibility. Rave tradition opened its doorways to a a lot vaster part of girls and boys who would by no means have gone dancing in that approach earlier than. It was a brand new type of leisure, and a youth tradition changing into mass leisure.”

Whereas the post-punk music-and-fashion scene had emanated extra from an “art-school” milieu, argues McRobbie, the rave scene at its peak was a much wider motion that grew organically from financial and social circumstances. “The working-class rave scene was an escape from the mundanity of post-industrial Britain, the place the expert labour market had declined. Rave gave working-class children a way of freedom,” she says.

It was a way of empowerment, McRobbie continues, which was later echoed in Morvern Callar, the 2002 movie by Scottish director Lynne Ramsay, which starred Samantha Morton. “It is based mostly on a e book by Alan Warner,” says McRobbie, “and it is about working-class women in Aberdeen, stacking cabinets”. It charts a gradual awakening of the protagonist’s sense of company and self, and – like Day’s picture of Moss on the seashore – emanates a temper of escape, freedom in nature, and a way of risk.

Glen Luchford

Glen Luchford“The rave scene was a gamechanger when it comes to gender,” says McRobbie, whose e book Feminism, Younger Ladies and Cultural Research traces the evolution of British subcultures from the Nineteen Seventies. “For boys, it was a brand new second of emotional, non-aggressive sexuality, partly due to the [drug] ecstasy, and the expression of emotions of affection and pleasure, and dancing for 5 to seven hours continuous, which boys would have carried out earlier than in homosexual or queer areas like Heaven in London. However in your common working-class boy to get pleasure from that bodily pleasure, openness and freedom, that was new. And for women it was a time of getting in contact with their bodily our bodies, too, dancing for hours.”

However regardless of the “summer season of affection” headline on The Face’s 1990 cowl, in line with McRobbie, this cultural second within the UK had nothing a lot in widespread with the unique Sixties Summer season of Love within the US. “Sociologists would not put these two actions collectively,” she says – the hippy Summer season of Love in San Francisco in 1967 was “qualitatively totally different”. “[The rave scene] was not related to an overtly political agenda. The San Francisco Summer season of Love was a time of social change that grew from Berkeley College and was pro-civil rights. It was overtly political and, with [Allen] Ginsberg concerned, literary.”

Younger fashion rebels

If there was a precursor of the British rave motion, it was the Swinging ’60s, which had been imbued with a temper of liberation and the breaking down of previous hierarchies. “The Swinging ’60s had been related to a liberating up and a breaking down of obstacles, at school, sexuality and gender,” says McRobbie. “It was designer Mary Quant [creator of the mini skirt], the Capsule. Doorways had been opening, and for working-class younger girls it was an vital time of pleasure and freedom, notably in city centres similar to London and Glasgow.”

The It woman of that second was the gamine, teenage mannequin Twiggy – along with her waifish determine, cheeky smile and working-class origins. Bicker informed The Observer: “Kate hadn’t been modelling for very lengthy however, even in her awkwardness, she had that factor about her that Twiggy had within the 60s, a freshness that matched the instances.” She was, in the way in which she outlined her period, Moss’s predecessor – together with the late Marianne Faithfull, the “wide-eyed poster woman for the Swinging ’60s“, who later in life grew to become good pals with the mannequin.

Inez & Vinoodh/ courtesy of the Ravestijn Gallery

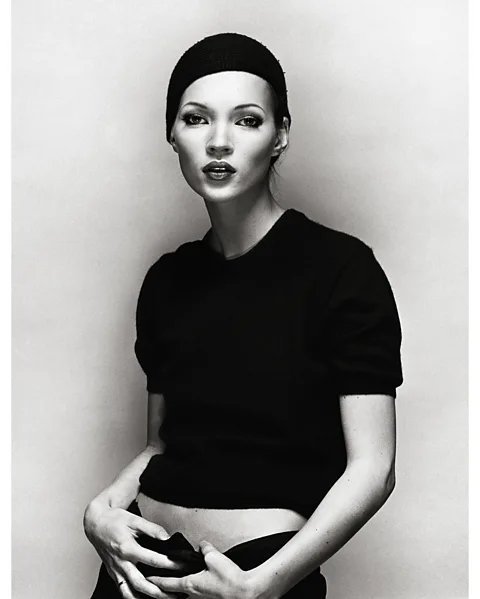

Inez & Vinoodh/ courtesy of the Ravestijn GalleryIt wasn’t lengthy earlier than the brand new aesthetic sparked by the summer season of affection shoot was influencing the business world, most noticeably in promoting campaigns by Calvin Klein with Moss for Obsession, and with Moss and Mark Wahlberg for the model’s underwear. In subsequent points, The Face continued to mirror the optimistic feeling concerning the decade forward – one cowl story shot by Day, and titled Younger Model Rebels, featured “5 faces for the 90s” with Moss, Rosemary Ferguson, Lorraine Pascale and different fashions who departed from the 80s “glamazon” norm. “After the supermodels, a brand new era is coming by means of with new concepts and angle” mentioned the introduction.

The subsequent time the Moss-Day pairing caught the general public’s consideration was with a 1993 trend story for British Vogue, wherein a really skinny Moss posed in underwear in a downbeat bed room. They had been once more defiantly unglitzy photographs, however this time – maybe due to the context of the venerable journal wherein they appeared – they provoked outrage. Grunge trend, waif fashion and “heroin stylish” grew to become phrases used within the British tabloid newspapers.

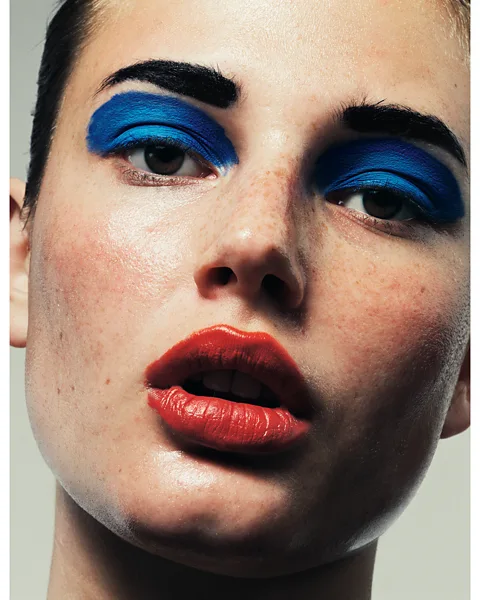

The Face was quickly shifting on to its subsequent part of the 90s – a succession of recent lads and ladettes, grunge and Britpop bands, and edgy younger British artists (identified collectively as “the YBAs”) all adorned the covers of big-selling problems with the journal, which from 1993 had a recent look, courtesy of Swillingham, the brand new artwork director. “There was a form of shift. From actuality to anti-reality, know-how and retouching, a extra kinetic, vibrant really feel,” he says. Swillingham commissioned photographers similar to Norbert Schoerner and Elaine Constantine, and the ensuing aesthetic was, once more, quickly adopted by the business world, with quite a few advertisements influenced by the colour-drenched, hyperreal fashion – notably a 1995 advert for Levi’s.

Elaine Constantine

Elaine ConstantineNew Labour was on the horizon. The Face was, says McRobbie, central to the “post-industrial inventive economic system, which was welcomed by Tony Blair and New Labour”. In 1997, artists, pop bands – together with Oasis – and trend people had been invited to 10 Downing Road by then British Prime Minister Blair. In the identical 12 months, Liam Gallagher and Patsy Kensit adorned the entrance cowl of prestigious US journal Self-importance Truthful with the coverline “London swings once more”, and the YBAs’ Sensation exhibition confirmed on the Royal Academy. Cool Britannia was born. “Simply because the Swinging London of the Sixties was a second of nice creativity and entrepreneurship, so was the Nineteen Nineties,” says McRobbie.

Then and now

Some have argued that the late 80s and early 90s rave motion in Britain was a second of acutely aware rebellion and egalitarian protest, a uniquely anarchic outpouring with its hedonistic, unruly origins within the nation’s chaotic and distinctive people rituals. It’s argued that it was a coming collectively of all genders, races and courses, and a big motion that resonates now – and has loved a latest revival. For others, it’s a collective reminiscence of pleasure. There isn’t any doubt the motion drew from a broad sweep of society – its adherents gathered from far and vast, from the soccer terraces, the suburbs, the internal cities, scholar campuses, the house counties. And positively, there have been protests across the introduction by the federal government of a invoice introduced in to finish unlawful raves.

Nonetheless, in line with McRobbie, rave was not a motion about concepts or politics. “The rave scene and the waif look weren’t political. The motion developed and have become about jobs and entrepreneurship, ultimately changing into the inventive industries in trend, music and extra. The legacy of The Face is that it kickstarted a precious – to the economic system – movie star tradition, huge industries and sponsorship offers.”

Lee Swillingham echoes this: “Style obtained industrialised within the 2000s, manufacturers obtained greater, and had been purchased out by huge teams. Excessive trend grew to become industrialised, and The Face was a part of that change. The journal began getting extra promoting, although we had been nonetheless outsiders.” This part in popular culture of the late 2000s and 2010s – which was dominated by a dirty, hedonistic look, and the sounds of bands like The Strokes and The Libertines – was later revived and reincarnated within the 2020s because the Indie Sleaze aesthetic.

David Sims

David SimsSadly photographer Corinne Day died from a mind tumour in 2010 – her images have been exhibited on the V&A, Tate Trendy, Saatchi Gallery and Photographers’ Gallery, amongst others. Most of the different names related to the style and pictures of The Face grew to become central to the fashion-celebrity industrial advanced – not least, in fact, Kate Moss, as iconic as ever. Swillingham went on to work at Vogue with Edward Enninful (who had been at fellow fashion journal ID). Photographers together with Ellen von Unwerth, Nigel Shafran, Kevin Davies, David Sims, Glen Luchford, Juergen Teller, Inez & Vinoodh, Elaine Constantine and others went on to have worthwhile careers within the business world, “on the centre of the up to date trend trade” says Swillingham, who’s now marketing consultant artwork director of Harper’s Bazaar Italia and has his personal inventive company, Suburbia. As Bicker – now a world, award-winning inventive director – places it: “Finally the one approach the trade may take some management over the younger disruptors was to embrace its protagonists.”

It’s maybe tough to think about now in our digital age, however there was a way of cultural cohesion about this time – and the way in which it was distilled and chronicled – that we can’t see once more. As McRobbie places it: “The Face marks out a pathway to social fragmentation. There was a coherence which was spectacular about The Face, and that has been dismantled within the digital age, which is a loss.” Swillingham cherished the “ephemeral” nature of issues then, and remembers his time at The Face as essentially the most thrilling job he ever had: “We did not have time to consider it, we had been in it.”