This week we’re going to do one thing a bit foolish, partly as a result of I’ve to organize for and journey to an invited workshop/speak occasion later this week and so don’t have fairly the time for a extra regular ‘full’ submit and partly as a result of it’s enjoyable to be foolish generally (and we’d study one thing).

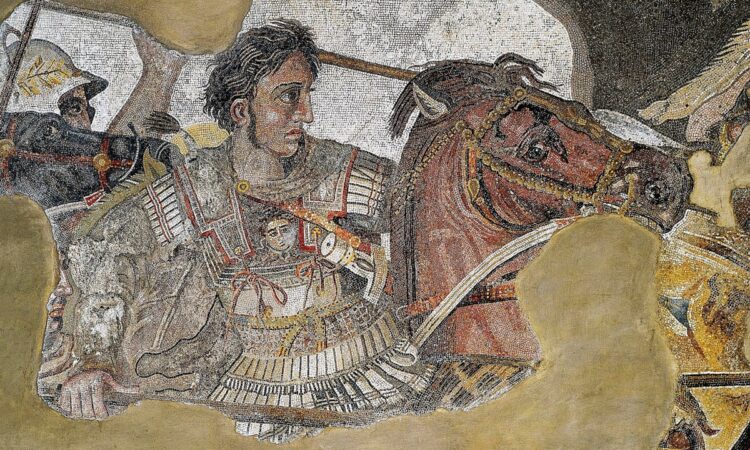

One of many customary pop-history counter-factuals that one sees engaged on historical navy historical past is a few model of “What if Alexander the Nice went West as an alternative of East?” It has come up fairly a number of instances right here within the feedback! And naturally we must always start by noting the query is itself a bit foolish. Alexander didn’t go East on a lark, his invasion was deliberate even earlier than he grew to become king and certainly when he grew to become king a Macedonian military was already in Anatolia laying the logistical predicates for his invasion. Alexander thus wasn’t able to essentially determine instantly to ‘go West’ nor would it not have made a lot sense to.

However I feel we will nonetheless ask this query in fascinating ways in which discover the character of our proof (notably its weaknesses) and likewise the challenges of conquest that lay past successful battles. Although earlier than we leap in, it’s price noting that we’ve achieved two collection related to this one: a two-part evaluation of Alexander the Nice (I, II) and a dialogue of the fight efficiency of the Macedonian phalanx (as a element of Hellenistic armies) in opposition to the Roman legion of the Center Republic, in an absurd variety of elements (Ia, Ib, IIa, IIb, IIIa, IIIb, IVa, IVb, IVc, V). We’re going to reference each right here.

However it is crucial, to start with, to determine when Alexander is “going West” (by which we imply ‘to Italy’). It is a extra sophisticated query you then would possibly initially suppose. The primary answer is, after all, to ship Alexander west in his lifetime, both at the beginning of his invasion (334) or on the finish of his life (323); the issue, to be frank, is that we don’t know practically as a lot as we’d like concerning the navy state of affairs in Italy in that interval although. We will assemble a fundamental narrative of the foremost wars (see beneath) however questions of military measurement, composition and even management are sometimes fairly fuzzy that early.

The tempting answer is to maneuver Alexander ahead a number of a long time chronologically to the place we will be extra assured concerning the type of opponents he’ll face, however the issue right here is that Alexander goes to face a very completely different Italy in, say, 290 than in 323. That stated, as we’ll see in a minute, we mainly know what would occur if time-traveling Alexander arrived in Italy round that point as a result of in 280 that mainly occurs: Pyrrhus of Epirus, usually considered probably the most gifted common of his era, main a Macedonian fashion military, invades Italy, resulting in the Pyrrhic Struggle (280-275). Our sources at this level are nonetheless not wonderful, however we all know the end result and might cause from that to a level.

Lastly, I feel people generally strategy this query in another way: they need a grudge-match between Alexander the Nice and a ‘absolutely shaped’ Roman Republic, as a result of what they need is to essentially reply ‘who was the very best at conflict in antiquity.’ From the historian’s perspective, that’s a bit foolish, after all: being ‘good at conflict’ is, to a level, delicate to context. That stated, the chronological divide right here turns into decently massive (a few century), however the technological divide isn’t all that significant – Alexander-style armies within the late third century had been nonetheless very a lot a factor! So the query may additionally be, basically, “what’s an Alexander-like determine went West round 218?” That’s additionally an fascinating query, however I feel truly fairly simple to reply as a result of our proof for this era is significantly better and factors very strongly to a conclusion.

So we will take care of every of those situations in flip and have a little bit of enjoyable with it. As we’re going to see, every situation not solely modifications the strategic state of affairs, it additionally modifications our confidence, the diploma to which our proof for the state of affairs in Italy is comparatively clear.

However first, in contrast to Alexander, I can not fund my campaigns via the neat expedient of looting all the Persian treasury at Persepolis. So if you wish to supporting this ACOUP marketing campaign, you possibly can contribute your tribute by supporting the venture on Patreon. And if you would like updates each time a brand new submit seems, you possibly can click on beneath for e-mail updates or comply with me on Twitter (@BretDevereaux) and Bluesky (@bretdevereaux.bsky.social) and (much less incessantly) Mastodon (@bretdevereaux@historians.social) for updates when posts go reside and my common musings; I’ve largely shifted over to Bluesky (I keep some de minimis presence on Twitter), provided that it has turn into a significantly better place for historic dialogue than Twitter.

Strategic State of affairs in 334

So for our first situation, we’re assuming Alexander goes West as an alternative of East in 334, invading with the identical military he introduced into Asia. Naturally our sources don’t totally agree on how large it was, besides that it was round 40,000; I don’t need to get too deep into the weeds on this query. Arrian stories 30,000 infantry and 5,000 cavalry (Arr. Anab. 1.11.3), which if we maybe add Parmenio’s advance pressure of roughly 10,000 (Polyaenus 5.44.4) we get the 40,000 infantry and 5,000 cavalry reported in another sources (e.g. Plut. Alex. 15.1). When it comes to composition, Diodorus (Diod. Sic. 17.17) stories 12,000 Macedonians within the phalanx, one other 12,000 Greek heavy infantry (allied and mercenary), and eight thousand lighter infantry (Thracians, Illyrians, Agrianians, archers and so forth), which provides as much as 32,000 infantry (of which 24,000 is heavy). Bolstered over time, Alexander’s heavy infantry element ‘tops out’ round 31,000 for the Battle of Gaugamela (331).

So let’s say Alexander has a military of round 40,000, with 5,000 cavalry and a heavy infantry core of roughly 24,000. He can get some reinforcements however largely has to make do with the military he has: minor losses will be changed, catastrophic losses can not. That’s our ‘benchmark’ to measure in opposition to. Let’s additionally assume Alexander has achieved some diplomacy upfront and maybe secured some type of settlement – as Pyrrhus will later do – with the Greeks of Southern Italy, so he can land his military safely, maybe close to Tarentum, and rely on the Greeks of Apulia to initially help him.

What’s the form of the strategic drawback he faces?

Properly, the excellent news is that Italy is fragmented on this interval. The unhealthy information is that Italy is fragmented on this interval. Alexander will not be dealing with one strategic drawback however half a dozen.

The drawback (for us) goes to be estimating the dimensions of every of those opponents. Now we have Livy right down to the 290s (Polybius doesn’t begin till 264) and bits of different sources (Dio, Diodorus, and many others) however these don’t give us a variety of clear numbers, partly as a result of our sources don’t know. The Romans solely began writing their historical past within the late third century, in spite of everything, and Livy appears profoundly confused by how the Roman military is even structured in 338 (Livy 8.8, a famously confounding passage during which Livy is confused and likewise the textual content is corrupt). Livy can be pretty open that early Roman historical past is stuffed with invented triumphs, unlikely tales that remodel defeats into victories and different ‘patriotic’ fibs, a lot in order that he has hassle untangling them. Nonetheless, we will no less than make a strong effort of an order-of-magnitude estimate of Italy’s navy powers in 334.

We will begin with the Romans (however Alexander gained’t). In 334, we’re 4 years on from the top of the Second Latin Struggle (340-338) however we haven’t but began the Second Samnite Struggle (326-304). Because of this, the Romans management Latium and Campania, however haven’t but moved in earnest into the mountains to the north-east (Umbria) or south-east (Samnium). The Roman census most likely totals round 165,000 grownup males (on the census figures, see Brunt, Italian Manpower (1971), 13 for the related sources), however a lot of the Latins and Campanians are nonetheless socii. Livy claims that by this level the Romans are enrolling 4 legions yearly (round 20,000 males) after which usually doubling this with the Latins (and different socii) for the standard subject military of round 40,000 (Livy 8.8.14-15). Given our census knowledge and every thing else we all know, I feel that’s believable and goes to be our baseline.

However Alexander, touchdown in Tarentum, isn’t going to get straight-away to the Romans, as a result of the very first thing in his means are as an alternative the Samnites. The Romans are going to combat two fairly brutal wars with these fellows (The Second and Third Samnite wars, 326-304 and 298-290) within the close to future, however they haven’t but, so the Samnites are nonetheless unbiased. Their society is grouped into pagi (a rural district; suppose one thing like our non-state armies by way of group) that are self-governing, however they accomplice collectively for bigger wars. The Samnites had been powerful hill-fighters whose armies made use of sunshine and heavy infantry, together with pretty succesful cavalry. When it comes to their navy energy, the one factor we all know is that it takes the Romans three and a half a long time to subdue them and the Samnites win some main battles in all of that. One late indicator we now have that’s helpful is that Livy represents the mixed Samnite and Senones pressure at Sentinum (Livy 10.27) as even in measurement to a 40,000 man mixed double-consular Roman subject military. By that time, the Samnites had been preventing fairly some time and this battle was fought in Umbria (of their allies territory, slightly than their very own) so this probably isn’t their complete pressure, however a lot of it. On the stability then, the Samnites appear to be roughly equal in navy energy to the Romans.

Subsequent up, transferring north, we now have the Etruscans, who’re additionally not but subdued by Rome. The Etruscans had been organized into city-states, however just like the Samnites typically shaped as much as combat collectively in bigger confederations, with a heavy-infantry centered pressure. When it comes to efficient navy energy, we all know that in 298 the Etruscans might go toe-to-toe with a serious Roman subject military, at Volterrae (Livy 10.12) and produce a bloody, attritional draw. The Romans will finally win this contest too, after all, however I feel it’s honest to evaluate the Etruscans as not that a lot weaker than our Romans in 334.

To their north, we now have the Gallic peoples of Gallia Cisalpina, notably within the Po River Valley, with the important thing peoples being the Boii, Insubres and Senones. These had been additionally fairly militarily vital polities, organized alongside the ‘barbarian tribal’ strains we’ve mentioned earlier than, however it’s exhausting to get their precise energy. Solely the Senones are at Sentinum (Livy 10.26.7) however we’re not given their numbers damaged out. By 225, an alliance of the Boii, Insubres and one other polity, the Gaesatae are going to subject a military that Polybius stories as 50,000 infantry and 20,000 cavalry (Polyb. 2.23.3) however that is each most likely an exaggeration and likewise I’m unsure such a big pressure might have been fielded a century earlier. There’s an inclination within the 300s and 200s, seen within the archaeology, for a considerable growth of the ‘navy’ class in Gallic societies, with poorer males being pulled into armies, a course of which was not full in 334.

However these Gallic peoples are nonetheless a considerable pressure, able to threatening any of the Italic powers to their south. Maybe extra apparently, we know how Greek, Macedonian and Hellenistic armies are going to carry out in opposition to the Gauls after they meet them in amount starting in 281: they’re going to have a tough time. Gallic armies, transferring into Greece and Macedonia are going to smash a Macedonian military lead by Ptolemy Keraunos, bust via a Greek effort to carry Thermopylae and attain, however most likely not sack, Delphi. One other group, the Galatians, are going to spend a number of years rampaging in Anatolia earlier than being settled in a area they’d give the title to: Galatia. Hellenistic armies actually generally win in opposition to Galatians – Antigonus Gonatas and Attalus I each achieve this – however they don’t at all times win, suggesting Gallic armies had been an actual menace, even to a Macedonian-style pressure.

And at last, we have to look south: any main invasion of Italy from Greece and Macedonia was probably to attract the eye of the 2 powers in Sicily: Syracuse and Carthage. Syracuse and Carthage had been preventing backwards and forwards over Sicily on and off since 480 and each might increase substantial forces. Sadly, our principal supply for lots of that is Diodorus Siculus and he tends to guide with numbers for these battles that are implausible. I gained’t undergo all the numbers right here: J. Corridor, Carthage at Struggle (2023) offers a really succesful, up-to-date, digestible (if a bit dry) survey of those wars. However the upshot is that armies of between 30,000 and 50,000 are reported incessantly sufficient to counsel that each Carthage and Syracuse (the latter with Greek allies) might ‘play ball’ on this vary if critically threatened on the island. Additionally they each have pretty highly effective navies on this interval, typically placing out fleets of 100 to 200 ships. Carthaginian assets shall be far extra huge than this within the First (264-241) and Second (218-201) Punic Wars, however we will’t assume that form of navy energy is obtainable to them in 334 for a conflict over Sicily. Nonetheless, both Carthage or Syracuse (the latter main a coalition of native Greek cities) might most likely subject a big sufficient military to demand Alexander’s undivided consideration.

We’ve left some people out (the Umbrians and Lucanians, most notably) however I feel we now have, roughly our ‘main gamers.’ And what we now have is an Italy-and-Sicily with not one however six main powers, of roughly equal measurement and navy functionality: the Samnites, the Romans, the Etruscans, Carthage, Syracuse and a attainable multi-polity Gallic coalition. All of whom can put a big sufficient military within the subject to require Alexander to deliver basically his complete expeditionary pressure to combat them.

Situation 1: Alexander Invades in 334

As you possibly can inform from above, that is our lowest confidence-level situation as a result of we merely have a variety of question-marks by way of the pressure Alexander is prone to face. However I feel we will have a look at the probably circumstances and chart out a number of broad potentialities for the way issues would go. First, after all, we now have to imagine Alexander: a really gifted commander with a extremely succesful military that’s usually going to win nearly any winnable battle. Even then, Italy on this interval is a tough nut to crack; Alexander can most likely do it (no less than for some time), however he might need he hadn’t.

The instant drawback is obvious with a fast look up via these numbers: slightly than one Persian Empire with a single Nice King and a collection of subject armies, Alexander is dealing with six opponents, every of which most likely has sufficient navy energy to satisfy Alexander within the subject. That truth is vital: none of the important thing polities listed below are so weak that they’d have to easily give up upfront and nothing about their cussed resistance in opposition to the Romans suggests {that a} roughly 40,000 man military of any description can be sufficient to get them to easily fold.

However past this, I feel, uncertainty assails us. As famous, our greatest indicator of how the Roman military fought on this interval (Livy 8.8) is an absolute mess that’s functionally unsalveagable. It’s clear that Livy, no less than, thinks that by this level the Roman military features in its three battle strains of heavy infantry and there’s no cause to suppose that’s incorrect. However past that, it’s exhausting to understand how armored they might be or the exact construction of the formation as a result of – once more – Livy 8.8 is a multitude (and the sources on the ‘Servian Structure’ are much more anachronistic and messy). So we will most likely say the Romans are using their heavy infantry military, composed of legions, led by consuls, however past that unpacking its tactical capabilities is troublesome. Which suggests it’s exhausting to know precisely how it will fare, this early, in opposition to a Macedonian-style military.

However we will converse to among the strategic and operational problems Alexander faces. Specifically, Alexander going West is in actual hazard of turning into trapped in a whack-a-mole drawback, sophisticated by his logistics. Within the East, Alexander relied closely on cities ‘surrendering upfront,’ submitting to his authority and giving him provides in trade for getting him to maneuver on out of their territory. Certainly, his logistics don’t remotely work with out this; if each metropolis alongside the road of Alexander’s march resisted, his expedition would actually have failed. However that habits makes sufficient sense for cities that hadn’t been actually unbiased in centuries, for whom massive imperial armies transiting previous them was a frequent sufficient prevalence.

However fourth century Italy isn’t like that: it’s a mess of defended, fortified cities that tend to ‘maintain out’ in opposition to raiding and even sieges. We all know they’ve that tendency, as a result of they typically do it: in opposition to the Romans, in opposition to Pyrrhus, in opposition to Hannibal. Likely Alexander would attempt to discourage this behavior in the identical means he did within the East: exemplary brutality in opposition to cities that held out. However the Romans and Carthaginians try this too, and it doesn’t result in swift, lightning advances!

The issue that poses is certainly one of pace and logistics. Let’s say Alexander arrives in Tarentum in 334. His subsequent cease is transferring north into Samnium and we will simply assume the Samnites roll out for a pitched battle (they completely would; the Samnites have testy relationships with the Greeks) and we’ll assume – Alexander being Alexander – they lose, at which level the Samnite pagi, awed by Alexander’s energy, would possibly submit. That allows him to cross the Appenines in the direction of Campania and the Romans. So in 333 he descends into Campania, we’ll assume he smashes the Roman subject military that can actually be there to greet him after which…nothing. The cities of Campania don’t give up upfront and provide him. So he’s compelled to besiege Capua and maybe Neapolis (Naples), as a result of he must safe this space in an effort to draw provides to help a transfer north into Latium. However Alexander has succesful engineers and a military that may do siege works, so he cracks the defenses of a number of main cities to safe the area. So by 332, he’s prepared to go into Latium; he faces one other subject military, smashes it and now he has to calm down and besiege no less than Rome. Roman assets being what they’re, even having smashed a pair of Roman subject armies, town is probably going nonetheless defended, so he’ll should take it in a troublesome siege. He would possibly as an alternative decide to barter.

By this level, chances are high fairly good the Etruscans are getting ready for his arrival and presumably aiding the Romans and chances are high equally good the Carthaginians are involved about this Greek-speaking invader of their sphere of affect. Let’s say Alexander will get the Romans to lastly submit by the top of 332, by which level he’s dealing with open conflict with the Etruscans in 331. Besides, by this level, he hasn’t had significant forces in Samnium in three years and he’s clearly absolutely occupied within the north. So the Samnites revolt and by this level the Carthaginian navy has pushed Alexander’s ships from the ocean. So he turns south to re-conquer the Samnites and hop to Sicily to attempt to shut down the Carthaginians, with Syracuse’s assist with cash and provides. That’s sluggish work – Carthage retreats to their coastal fortresses, which should be stormed, one after the other.

After all, the second it appears to be like like Alexander would possibly win, say, in 329 or 328, Syracuse’s pursuits right here instantly recalculate in opposition to him, in order that they lower their help and now Alexander has to combat them too. Besides at this level, Alexander hasn’t been in Latium for 4 years…so the Romans revolt and the Etruscans with them. And he nonetheless hasn’t fairly nailed down the Samnites and hasn’t even touched the Gauls. In the meantime, his conflict with Carthage is popping intractable in the identical means Pyrrhus’ conflict did: he has little capability to assail Carthage’s useful resource base in North Africa (as a result of Carthage can defeat his navy) or to cease Carthage from resupplying its coastal bases.

In brief, even when we assume that Alexander can commandingly win all of the battles, the slower tempo of warfare in a context the place everybody has armies and everybody tries to carry out and everybody goes again to conflict after they’ve regenerated forces makes a ‘lightning’ Alexander-style conquest extraordinarily troublesome. This was an issue that actually solely cropped up in the direction of the top of the actual Alexander’s reign and even then solely after he reached the Iranian Plateau, however in Italy it will be an instant drawback, as a result of Alexander had an opportunity to accumulate momentum and great looted wealth.

However because the conflict drags on – once more, we’re simply assuming Alexander is successful one lopsided victory after one other – he begins to run into one other drawback: cash. Alexander’s troopers count on to be paid and so they count on to be paid in silver cash. Alexander was already considerably in debt when he took the throne (Philip II’s conquest of Greece was costly), so he wants conquest to pay and he wants it to pay in silver. And right here he has an issue as a result of within the 330s and 320s, the Romans barely use coinage in any respect, and what bodily ‘cash’ they’ve is generally in bronze. There’s some silver coinage circulating round Italy, largely Greek cash in Southern Italy and the Etruscans mint a little bit of silver coinage, however a lot of the coinage was in bronze and even then, in comparison with Greece, there wasn’t that a lot of it. Worse but, nothing I’ve seen within the grave items of this or earlier durations suggests Alexander was going to seek out something just like the mintable steel wealth he would want at this level both. A lot of the fancy grave items I can recall from this era are – you guessed it – in bronze (weapons, armor, instruments), not silver or gold.

Once more, it’s not that there’s no silver and gold, however Alexander wants big portions of silver to maintain his navy machine churning and the Italian financial system of the fourth century BC is just not set as much as furnish that. A giant a part of the explosion of Roman silver coinage within the Center and Late Republic goes to be silver coming from Spain and the East.

So on the one hand, assuming Alexander can win all of his battles decisively and with few casualties, he can actually pressure some submissions however truly holding Italy goes to be exhausting: past each enemy is one other enemy, which has sufficient navy pressure to demand Alexander’s complete military, that means he can’t drop off greater than token garrisons as he strikes. The opportunity of ending up slowed down in enjoying whack-a-mole as beforehand ‘subdued’ polities unconquer themselves whereas Alexander is off elsewhere is excessive – that tendency was a part of why the Roman conquest of Italy took so lengthy! However Alexander can’t take ceaselessly as a result of his monetary clock is ticking quick: he wants a fast conquest to maintain his military funded. However Italy isn’t an enormous pot of silver guarded by a single Nice King and his fragile military, however slightly a smaller pot of bronze, being fought over by half a dozen polities, every with their very own military and grudges (and all of them, annoyingly for Alexander, simply sturdy sufficient to compel his full consideration).

The way you sq. these circles is, after all, the unknowable a part of the counter-factual. For my very own half, I feel Alexander might most likely have overrun a lot of Italy, however would have ended up badly slowed down, compelled to spend time consolidating his management and establishing methods of extraction and settlement. He would possibly nonetheless reach Italy, nevertheless it wouldn’t be the lightning conquest he had from 334 to 330 the place he overran all the Achaemenid Empire. It might be extra just like the wars from 330 to 326, the place he slowly floor out victories in Bactria and alongside the Indus, however with out the benefit of getting already looted the Achaemenid treasury. And naturally his military famously misplaced persistence with the sluggish wars of the again half of his marketing campaign and mutinied in India. We’d think about his military right here working out of persistence a lot earlier.

That stated, we’ve made a variety of assumptions and left a variety of query marks, as a result of there’s only a lot we have no idea this early in Italy’s historical past: we will solely guess on the navy energy of a lot of the main gamers, or their ways, or their gear, or the probability they’d maintain out.

However we will study a bit extra if we roll the clock ahead to 280 and ask how Alexander would fare then.

Situation 2: Alexander As an alternative of Pyrrhus

Shifting ahead to 280, our uncertainly shrinks rather a lot as a result of we will now say one thing about how Roman armies would possibly work together with Macedonian-style armies, however after all the tough factor for our evaluation is that the strategic state of affairs has additionally modified a good bit.

The principle culprits listed below are the Second (326-304) and Third (298-290) Samnite Wars. The Second Samnite Struggle had confirmed Roman management of Campania, but in addition over numerous central Italy, with a number of communities both annexed into Roman citizenship (generally as a punishment, meant to obliterate the earlier communal id) or folded into the rising ranks of the socii, most notably the Marsi, Paelingni, Fretani and Vestini, which superior Roman management all the best way to the Adriatic and possibly left Rome a transparent primus inter pares amongst powers in Italy. The Third Samnite Struggle is, for my part, considerably of a misnomer, as a result of it finally ends up a lot larger, with Rome confronting a grand alliance of mainly all the non-Greek polities in Italy: the Etruscans, Umbrians, the Senones (a Gallic individuals) and the Samnites in what I view as a ‘containment conflict.’ Roman victory in 290 meant absorbing the remaining Umbrian-speakers and the Samnites into the Roman system, and an incomplete however vital extension of Roman management in Etruria.

Consequently, Pyrrhus arrives to not discover the fragmented six-way scrum of 334, however as an alternative a quickly consolidating state system behind Rome (plus the Carthaginians and Syracusans in Sicily). Roman assets had been thus considerably better. Colonial foundations and annexations had practically doubled the citizen inhabitants, to round 290,000 (Livy 10.47; Per 11, 13, 14; as soon as once more see Brunt (1971), 13) and it positive looks like the entire quantity of socii had greater than stored tempo (at the same time as among the Latins have drifted into citizenship). We’re not but to the navy monster the Romans will construct by 264, however we’re getting there. The excellent news for our time-traveling Alexander is he now actually solely must beat the Romans to consolidate the peninsula; the unhealthy information is that he has to beat the Romans and there are actually a lot of them.

What makes this second illuminating for our query, nevertheless, is that the Romans truly combat a Macedonian-style Hellenistic military, led by Pyrrhus of Epirus. We’ve talked about these battles already, so no must reinvent the wheel; if you would like an much more detailed dialogue, there may be truly an excellent latest marketing campaign historical past on this one, P.A. Kent, A Historical past of the Pyrrhic Struggle (2020). On the one hand, Pyrrhus’ military is a bit smaller than Alexander’s – round 31,500 initially. However, it’s truly a good bit extra tactically complicated and complicated and so had some capabilities Alexander could not have, specifically conflict elephants (which the Romans had no expertise of) but in addition Pyrrhus’ efforts to create an articulated or ‘enallax‘ phalanx. And I feel we additionally shouldn’t overstate the hole in command capabilities right here: Alexander was an astoundingly succesful common, for positive, however Pyrrhus additionally has a fame within the sources as an distinctive commander, the very best of his era. It’s honest to guess that Alexander might need gotten a bit extra efficiency out of his military, however I don’t suppose we’re a unique in sort.

Pyrrhus’ expertise demonstrates vividly a variety of the issues we proposed above: the flexibility of Rome and Carthage to quickly reconstitute forces, but in addition the widely slower tempo of warfare in Italy, the place Massive, Decisive Victories didn’t trigger big swaths of cities to give up. After his first victory at Heraclea, Pyrrhus makes an attempt a form of ‘thunder run’ via Campania into Latium and inside a pair day’s march of Rome, however nobody surrenders (and even negotiates), forcing Pyrrhus to choose off Roman garrisons and cussed cities one after the other (beginning with Venusia and Luceria). The outcome was that the Romans had greater than sufficient time to reconstitute. He faces the same drawback with Carthaginian coastal garrison cities in Sicily.

Nevertheless it additionally hints at one thing we will’t be sure is true in 334, however whether it is, it’s unhealthy information for a west-facing Alexander in 334: even in defeat, Roman armies draw blood. Alexander’s success in opposition to the Achaemenids was essentially predicted on comparatively low casualties, on battles the place, if he gained, his losses can be minimal. Alexander reportedly loses simply 115 males on the Granicus (334), solely 150 killed at Issus (333) and a harder however nonetheless delicate 1,500-or-so losses at Gaugamela (331). These types of losses had been mainly rounding errors, probably swamped by losses to illness and different pure causes in his military and simply made up by the occasional complement of reinforcements. However Alexander additionally wanted these losses to be low, as a result of he didn’t have an entire lot of reserves. The one different Macedonian pressure of word was Antipater’s military again in Macedon, simply 12,000 infantry and 1,500 cavalry (Diod. Sic. 17.17.5). In brief, Alexander is preventing with one thing of a glass jaw – he will get away with it as a result of his opponents by no means land a extremely strong punch.

At Heraclea (280), Pyrrhus wins, however loses both 13,000 or 4,000 troops (relying on who you belief, Plut. Pyrrh 17.4; students desire the smaller quantity), which is already greater than Alexander misplaced in all 4 of his main pitched battles. At Asculum (279), Plutarch says Pyrrhus took 3,505 losses, whereas Diodorus claims 15,000; as soon as once more we desire Plutarch’s smaller quantity, however as soon as once more considerably greater than Alexander misplaced in all 4 of his main pitched battles. Pyrrhus’ losses on the draw of Maleventum aren’t clear – our sources are fairly unhealthy – however will need to have been considerably heavier than this. So when dealing with an skilled, battle-hardened Macedonian-style military commanded by the very best common of a era, the Romans frequently inflict extra casualties shedding than Alexander took in all 4 of his main pitched battles, mixed.

And that’s fairly the harmful blinking warning signal for both a time touring Alexander or – if we suppose the Romans would have carried out equally in battle in 334 – our 334!Alexander, as a result of Alexander can not actually afford to make up these losses, particularly if he additionally must be detaching troops to function garrisons. A state of affairs during which even in victory Alexander loses 10% of his military each battle would merely not be sustainable even within the comparatively close to time period for him, as a result of the ‘spine’ of Macedonian manpower was by no means all that strong. Certainly, the Macedonian free, citizen inhabitants might be roughly the identical measurement or smaller than the Roman citizen inhabitants in 334. It’s, after all, a lot smaller than the Roman citizen inhabitants in 280.

The query, which is unanswerable, after all, is to what diploma Alexander, by dint of being Alexander, would have been capable of keep away from these casualties. My very own view is that I don’t suppose he might have. Pyrrhus was a really succesful commander wielding a really succesful military; Alexander is likely to be higher, however I don’t suppose he’d be radically higher. As an alternative, as I’ve argued, the attritional Roman fashion of preventing was constructed to supply vital casualties, win or lose. Even spectacular victories just like the Battle of Cannae (216) and even profitable ambushes like at Lake Trasimene (217) lead to Rome’s victorious enemies taking significant losses. Hannibal loses extra males (1,500 to 2,500) ambushing the Romans by full shock at Trasimene than Alexander misplaced in any particular person pitched battle. The Roman system of preventing simply does that.

Assuming the assorted individuals of Italy fought in 334 the best way they did in 280 – and we aren’t seeing radical modifications in navy materials tradition (to the diploma we will inform) which might counsel they didn’t – Alexander’s westward highway is trying much more troublesome, as a result of he’d be dealing with way more substantial attrition. And his military merely can not tolerate these ranges of attrition. On stability, I feel that implies that a hypothetical 280!Alexander fails (once more, that’s simply Pyrrhus) but in addition suggests much more difficulties for our 334!Alexander, as a result of there’s no cause to suppose Rome’s armies in 334 are meaningfully tactically completely different than in 280.

Situation 3: Alexander at Cannae

Now we make yet one more big soar ahead, largely simply to exhibit the outer fringe of our potentialities: time-traveling Alexander the Nice preventing the Mid-Republican Roman navy system within the center or late third century (264 or 218).

And I included this largely as a result of it’s illustrative the best way during which the uncertainty which has dogged the earlier comparisons evaporates into near-certainty: Alexander is completely hosed. By the late-third century, our proof is significantly better: we now have a a lot firmer grasp on Roman assets, a whole description of their military and numerous well-documented campaigns testing Roman capabilities. No a part of what we see when the curtain lifts is favorable for Alexander.

As we transfer ahead, the strategic image modifications once more. Samnium, which revolted to hitch Pyrrhus, is kind of forcibly rejoined to Rome on the finish of the Pyrrhic Struggle, together with all of Southern Italy. By 264, the continuing Roman conquest of Etruria can be very full and has been for some time. We will inform Roman management in Etruria is extra firmly settled as a result of when Hannibal tries to get the socii to revolt, he will get some curiosity in southern Italy, however nearly none in Etruria. Consequently, by 264, the Roman mobilization monster is absolutely operational and we now have to imagine that Rome most likely has entry to one thing just like the roughly 700,000 males chargeable for conscription that Polybius says they’ve in 225 (Polyb. 2.24). Alexander’s military completely can not commerce casualties with that factor – the Romans have a full order of magnitude extra reserves than he does; he must run a fully immaculate collection of one-sided miracle victories and he wants a lot of them. Three, as Hannibal goes to point out us (actually 4 if we rely the Battles of the Higher Baetis in 211) isn’t sufficient and we all know that as a result of it occurred and the Romans steamed on via anyway.

And there may be simply, to be frank, no cheap likelihood of Alexander pulling that off. On the one hand, we’ve seen what Roman armies of the 280s and 270s do to Macedonian-style armies: they may not win, however they draw a variety of blood even when shedding. On the opposite finish of this era, we all know what Roman armies after 200 are going to do to each Macedonian-style military they meet: completely wreck it. The Romans combat 5 main battles with Hellenistic armies within the second century (Aous, Cynoscephalae, Thermopylae, Magnesia, Pydna) and win each single one decisively. Each choices are deadly to our time-traveling Alexander going west, as a result of his navy system can’t tolerate these sorts of losses.

I really feel pretty assured in saying an Alexander ‘going west’ in 218 would vanish like a pebble right into a pond: a number of ripples, shortly misplaced as his military is just swallowed by the assets and tactical sophistication of the Roman’s navy monster. We’ll come again to Carthage later this 12 months, however the Barcid navy machine, I believe, might have completed comparable outcomes (however word that this machine additionally didn’t exist in our earlier durations!). In any case, it very practically matched the Romans.

Alexander Within the West

So largely this has been a chance to suppose via the best way our imaginative and prescient of circumstances in Italy turns into progressively clearer from 340 to 218, together with a have a look at the altering political and strategic state of affairs.

However we will return to our counter-factual, “What if Alexander went West?”

Lots of the specifics of our reply is dependent upon how far we’re keen to venture backwards the certainties of the third century into the fourth. If Roman armies (and the armies of different Italian powers) in 334 behave like they did in 218 and even in 280, Alexander goes to have a really powerful time in Italy. However after all, we will’t be assured that we will ‘fill within the blanks’ of 334 with the ‘frog DNA‘ of 280 or 218 (and in some instances, we will be assured we will’t).

However I feel we will enterprise a number of conclusions. The form of lightning conquest Alexander achieved within the east in opposition to the Achaemenids might be not going to occur for our counter-factual Alexander within the west, even in 334 (or 323). Whereas every victory in opposition to the Achaemenids might internet Alexander monumental territory (and with it, a variety of money to pay his military), every thing we all know suggests Italy can be a sluggish, grinding operation.

That sluggish progress can be prone to blunt Alexander’s personal capabilities over time: because the preliminary conquests fail to offer sufficient of a money infusion to lavishly pay his military, Alexander goes to be compelled to pare again his pressure to what he can afford. That in flip threatens to pressure him to adapt to pre-existing mode of warfare in Italy, preventing grinding wars with smaller armies in opposition to polities that conflict repeatedly and regenerate navy capabilities shortly. Mixed with the whack-a-mole drawback mentioned above, it’s not exhausting to see Italy turning into a quagmire that consumes Alexander’s assets at the same time as he continues to win victories. If we assume – and on the stability, I feel that is the most certainly – that even when shedding, the armies of Italy inflict substantial casualties, all of those issues turn into a lot worse. Alexander would possibly effectively have discovered that after a decade of victories and grueling warfare, he had managed to make himself the grasp solely of Italy south of the Volturnus, with a extra tenuous overlordship over Rome and Latium – and an more and more fraught relationship with Carthage to the south and issues to the north within the Adriatic with the Illyrians, Pannonians and Dalmatians.

From there, his successors would possibly attempt to take the trail that Rome did, slowly however absolutely grinding down the peoples of Italy and welding them collectively into a bigger navy machine, however to be frank, the manpower of Macedon might be too restricted to maintain that venture and the politics of Greece too chaotic to allow Alexander or his successor the uninterrupted a long time they’d want to perform such a venture. It appears way more probably that the second Alexander dies – or is compelled to return to Macedon, maybe to take care of a revolt among the many Greeks – the entire venture comes aside. Alexander would turn into Pyrrhus a number of a long time earlier in the identical means Pyrrhus tried to turn into Alexander a number of a long time later.

However there’s an equally helpful remark right here: pre-Roman Italy couldn’t be subdued by a single lightning conquest and it wasn’t. As an alternative, the Roman alliance system was the product of many, sluggish, grinding a long time of conquest. Roman growth outdoors of Latium – the conquest and consolidation of which had been its personal lengthy venture from 501 to 338 – started in 343 and appears to have solely been actually accomplished within the 270s. That sluggish course of in flip partly explains why the Roman system was so sturdy underneath the pressures of Pyrrhus and the Punic Wars: every new neighborhood had been introduced into the system, one-by-one and stored in it lengthy sufficient for the system to turn into consolidated and customary. It was exactly as a result of Rome’s conquest of Italy wasn’t an Alexander-style lightning conquest that it was sturdy.

It’s not clear Italy might have been conquered every other means.