On the morning of three April 1953 workers reporting to the US Nationwide Bureau of Requirements (NBS) in Washington, DC, discovered a bouquet of two dozen carnations on the entrance gates. A card, hooked up with a white bow, learn: ‘In reminiscence of Dr. A.V. Astin and the traditions of the Nationwide Bureau of Requirements.’ Allen Varley Astin, the bureau’s director, had been compelled out days earlier by Sinclair Weeks, the brand new secretary of commerce in Dwight D. Eisenhower’s fledgling administration.

Astin’s dismissal got here after the NBS, the federal metrology laboratory, had examined and deemed ineffective a product branded ‘AD-X2’, an additive marketed as extending the lifetime of automobile batteries. Weeks, looking for to indicate assist for small enterprise, deemed the judgement reckless in gentle of the thick sheaf of testimonials praising the product. ‘The Nationwide Bureau of Requirements has not been sufficiently goal, as a result of they low cost totally the play of the market place’, he advised a Senate committee the day Astin’s ouster was introduced.

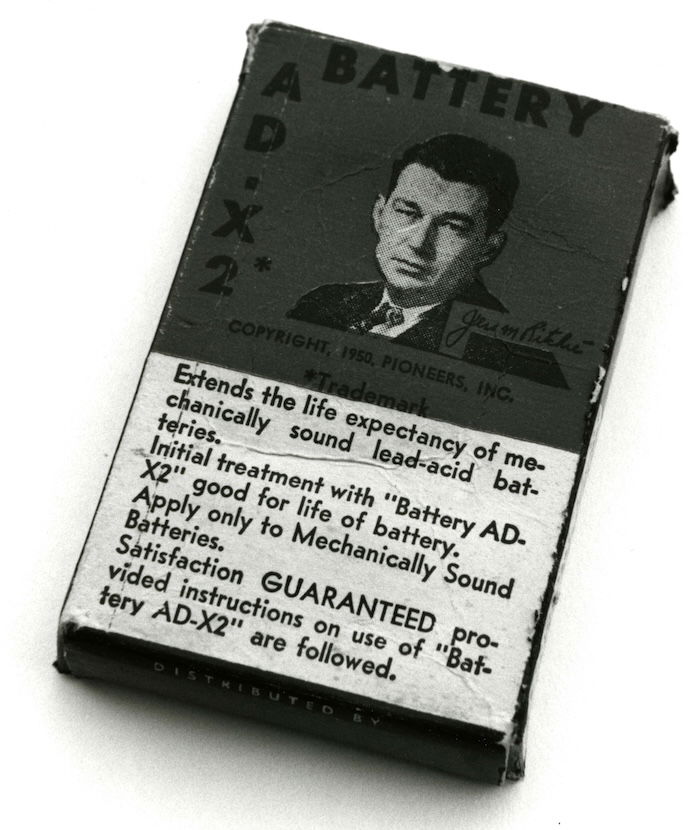

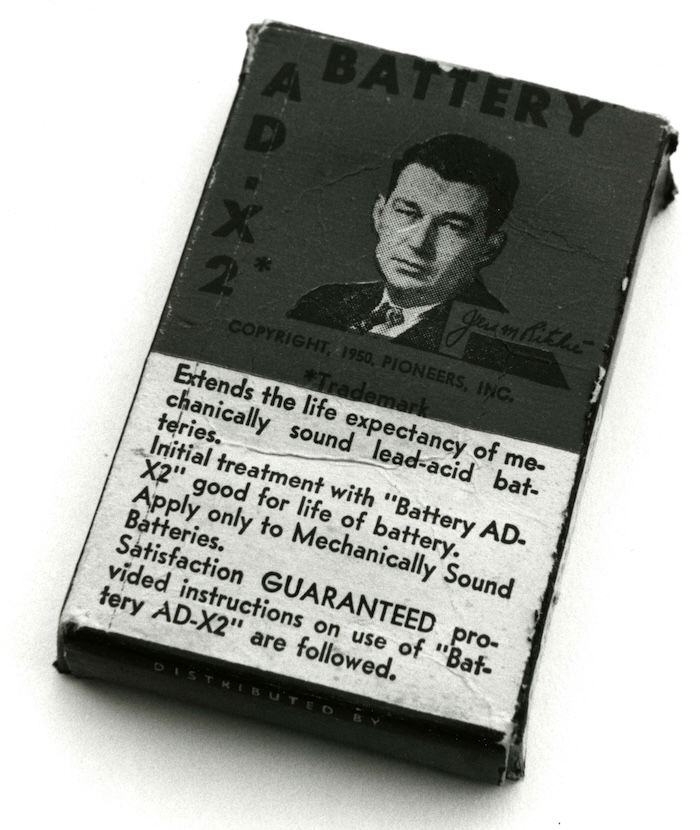

AD-X2, bought by Jess M. Ritchie, a charismatic former bulldozer operator, was a mix of salts designed to be blended right into a automobile battery’s electrolyte. The lead-acid battery grew to become customary in gasoline-powered vehicles round 1920 and motorists quickly got here to know battery bother as a well-known bugbear. Components, which purveyors claimed would revive useless batteries or prolong the lives of wholesome ones, proliferated. The NBS had examined dozens of nostrums of comparable composition and repeatedly declared them ineffective, and typically dangerous. Ritchie, although, remained indefatigable. Declaring NBS condemnations outdated and prejudicial to his product, he mounted a dogged political strain marketing campaign, asking his distributors to put in writing to their senators, lobbying members of the Senate Small Enterprise Committee, and pleading his case on to Weeks, who took motion.

The years after the Second World Conflict had been a golden age for American science. Scientists, flush with authorities cash, loved appreciable latitude in how they used it. However when Eisenhower took workplace in January 1953 as the primary Republican president in twenty years, questions arose about how that relationship may evolve. Within the nuclear age science was politically charged. American scientists welcomed the sources their new relevance introduced, however eyed the compromises that got here with transferring in political spheres warily. Astin’s firing got here at a essential juncture within the negotiation of postwar science-government relations, and it sparked a livid response. The mournful bouquet on the NBS gates was one small expression of a speedy and relentless response from the scientific group.

By the primary two weeks of April greater than 12 scientific organisations, together with the American Bodily Society, American Chemical Society, and American Affiliation for the Development of Science, launched public statements decrying Weeks’ actions. Scores of people wrote to Weeks and Eisenhower beseeching them to rethink. Scientists made comparisons with the ideological management of science exerted by Adolf Hitler and Joseph Stalin. ‘If we’re so cowed that we can not ally ourselves within the protection of science and scientific requirements of fact, we invite the destiny of the German scientists of the Thirties’, Harvard College’s Edwin Kemble warned his colleagues in Physics Right now. Behind the scenes, cooler heads – although no much less affronted – labored to exert extra refined strain on Weeks. Throughout the NBS, greater than 400 workers, citing impugned honour and cratering job satisfaction, threatened to resign if Astin was not reinstated. Earlier than two weeks had handed, Weeks agreed to go away Astin in place pending a evaluation by the Nationwide Academy of Sciences (NAS) – a concession that upheld the precept that solely the scientific group was certified to police its personal establishments.

All through the summer season of 1953, AD-X2 routinely featured amongst critiques of Eisenhower’s administration alongside his gentle contact with Senator Joseph McCarthy and the sharp elbows of his secretary of state, John Foster Dulles. Political cartoonists adopted the automobile battery as an emblem of political juice. Lastly, in October, two NAS evaluation committee experiences vindicated the bureau’s conduct and conclusions. Weeks invited Astin to remain on completely. Nearly concurrently, although, the Put up Workplace vacated its fraud order in opposition to Ritchie’s firm – issued in February however suspended days later – for ‘conducting an illegal enterprise by way of the mails’ and he was free to proceed promoting his product. All sides claimed victory.

For the bureau, that victory was notable as a result of it was so clearly political. That they had not satisfied the federal government to implement their laboratory findings in coverage, however had however succeeded in a wrestle for institutional autonomy. That success grew to become a template for a secure postwar relationship between science and politics, which survived the next seven a long time. Scientists, because the slogan went, had been ‘on faucet, not on high’ – however they loved appreciable management over the plumbing.

The AD-X2 affair had a protracted afterlife as a cautionary story in science-policy circles. David L. Hill, a nuclear physicist who testified in opposition to Lewis Strauss as successor to Weeks as secretary of commerce in 1959, after Strauss’ campaign in opposition to J. Robert Oppenheimer, leaned on the incident to strengthen his case in opposition to Strauss’ affirmation, declaring that, as interim secretary, Strauss had appointed a Ritchie ally to a key publish. In 1969 AD-X2 was the marquee case research in a congressional handbook designed to assist lawmakers navigate the tangled interface between science and politics. The affair formed the views of quite a lot of people who later served on the President’s Science Advisory Committee. For many years it remained a prepared reminder that though scientific consensus was inadequate to inspire coverage decisions, the independence of scientific establishments was sacrosanct.

That independence, the topic of heated battles by way of the spring and summer season of 1953, is now underneath direct assault within the US – as illustrated this August with the removing of the director of the Facilities for Illness Management and Prevention, which plunged the company into chaos and led to a wave of resignations. Scientists on the Nationwide Institute of Requirements and Expertise (as NBS is now recognized), the Nationwide Institutes of Well being, and different federal establishments are accustomed to the autonomy required to attract conclusions that may or won’t translate into coverage, however which kind a dependable foundation for informing it. That public-service mission, mixed with freedom of inquiry, has lengthy been a strong draw for personnel who might command increased salaries in business or higher status in academia.

The historical past of the AD-X2 affair is a well timed reminder that the newfound political relevance of science didn’t assure the autonomy of US federal scientific establishments, so important for attracting and retaining a proficient and pushed workforce. It needed to be fought for. Relative independence was the reward for sustained and efficient political motion. In 1953 scientists warmed to the combat to determine the precept of institutional autonomy. In 2025 they face the extra complicated problem of defending it.

Joseph D. Martin is Affiliate Professor of the Historical past of Science and Expertise at Durham College.