Emily Pictou-Roberts and Jess Wilton

In the Mi’kmaw language, puoin (boo-oh-in) refers to a shaman or witch. In Mi’kmaki — the realm we now name Atlantic Canada and components of Maine and Québec—these puoinaq (plural of puoin) are sacred figures who possess the power to shapeshift and to convoke the spirit world. In recent times, Queer and Trans Indigenous communities inside Mi’kma’ki have refocused the time period as a culturally particular idea of Two-Spirit id. In comparison with different Indigenous cultures throughout Turtle Island, the Mi’kmaq have skilled one of many longest colonial histories. Consequently, there stay few traces of gender nonconformity or queerness in conventional information on the East Coast. Nonetheless, with care, we will discover and reclaim traces of Queer and Trans Indigenous identities throughout these information and narratives. Impressed by Mi’kmaw Historical past Month, this installment of Queering Atlantic Canada troubles our understanding of area with Indigenous methodologies; it additionally provides a way to queering Indigenous historical past and tradition via the Mi’kmaw language and storytelling alongside our personal against-the-grain readings of the colonial file.

All through our exploration of Mi’kmaw queer tradition, we encountered a large number of obstacles—together with a shortage of each main and secondary sources. One of many few secondary sources emphasizes this dearth. In Joseph Randolph Bowers’ e-book Mi’kmaq Puoinaq Two-Spirit Drugs, Elder Dr. Daniel N. Paul writes the ahead. He discusses that “Two-Spirit gender and sexual variety probably existed among the many Mi’kmaq as one thing honourable and regular…However it’s possible you’ll not discover direct and clear written proof of both of those factors, relying on the place you look and who was doing the writing.” On this assertion, Elder Paul highlights a serious concern in decoding a Two-Spirit Mi’kmaw historical past: how would we strategy the few sources we uncovered? Collectively, we tried to bridge these points by combining worldviews as a Two-Spirit Mi’kmaw lady and former Mi’kmaw historical past interpreter, and a non-Indigenous historian educated in queer and Canadian histories. Our views inspired us to contemplate each Indigenous oral histories and storytelling as essential in sustaining and rekindling cultural practices and information all through historic and modern colonization. These oral traditions are greater than folklore, legends, fables, or myths; they’re elementary to understanding the wealthy historical past of the L’nu’okay (ul-noog), or The Individuals, within the language. As Mi’kmaw professor Trina Roache asserts in her thesis on pressured Mi’kmaw relocation: “oral historical past is an integral technique to unsilence the historic narrative of Indigenous Peoples.” It’s a methodology rooted within the distinct values and information programs of the tradition. Thus, making house for oral custom is a needed facet of reclaiming and disseminating Indigenous histories and methods of realizing, whilst we discover the colonial information.

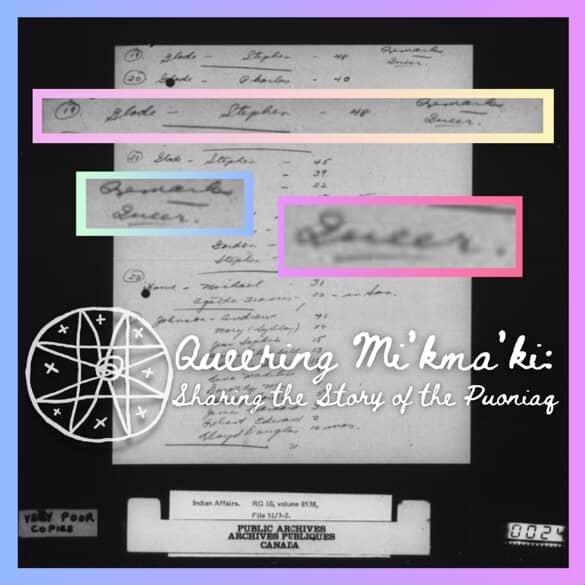

In 1950, H.C. Rice, the superintendent of the Shubenacadie Company (Division of Indian Affairs), tasked Tom Murray of Parrsboro with counting the “Indians” in Cumberland County for a census. Murray replied with a handwritten census, which he had organized and numbered by households, noting their identify, age, and remarks reminiscent of who they lived with or their marital standing. Considered one of these remarks is a uncommon instance within the historic file the place Murray categorizes one of many Mi’kmaq as “Queer.” Contemplating the opposite remarks, “Queer” is presumably included to clarify why the person lives alone, not like many others listed within the census, or maybe to differentiate them from one other particular person with the identical identify just a few traces under. Whatever the preliminary purpose for together with this comment, the characterization of this particular person as “Queer” signifies a few issues about Queer L’nu’okay histories and life tales, particularly inside the broader context of present storytelling and oral histories. First, it reveals that there have been queer people (who had been visibly identifiable by white neighbours) residing in no less than some areas of Mi’kma’ki within the Nineteen Fifties. We additionally know they weren’t the final, as John R. Sylliboy and Tuma Younger present fairly clearly with their very own tales and lived experiences. We are able to additionally assume they had been very probably not the primary because of the recollections of our Elders. For instance, Bowers explores an oral historical past that was instructed to him the place Two-Spirit Mi’kmaw had been the primary to greet the “white man” and introduced with them “sacred medication” (182-183).

This census file additionally begins to make clear the best way sexuality interplayed with colonial insurance policies and Canadian citizenship. Within the interval simply previous to this census, Roache identifies a “centralization coverage” which basically disrupted Mi’kmaw connection to dwelling and homeland, together with constructions of ni’kmaq (nee-gee-mah), or household, whereas making them legible to the state. Throughout Canada, different students have thought-about the interval between 1755-1950 a interval of assimilatory insurance policies. It’s probably that this census, accomplished by a white citizen of Nova Scotia, performed a component in cataloguing the province’s centralization insurance policies, the place household construction and kinship had been integral; this, in flip, made sexuality necessary in the best way it disrupted heteronormative conceptions of household inside neighborhood. Nonetheless, in 1950, the Indian Affairs department was switched from the purview of the Division of Mines and Sources to the Division of Citizenship and Immigration. Historians have famous that this alteration is necessary to the best way Canadian citizenship was constructed, inserting each new immigrants and natives in the identical class for assimilating residents. That is evident within the DIA’s Assessment of Actions 1948-1958, the place the general objective was for Indigenous peoples in Canada “to turn out to be totally collaborating and self-supporting members of the communities wherein they stay” (12). The interval additionally marks the start of The Purge, the place the Canadian authorities started the mass identification and expulsion of 2sLGBTQIA+ people from the navy and public service. At a time when the federal authorities was implementing concepts of Sexual citizenship and redefining the perfect citizen in postwar Canada, it’s potential that this comment of “Queer” additionally factors us in direction of an understanding of the best way Indigenous Queer people may need been affected by colonial insurance policies and interacted with numerous governmental and authoritative our bodies within the mid to late 20th century.

Whereas we’ve not encountered many recollections which may assist deepen our understandings of Two-Spirit kinship practices or Indigiqueer interactions with the Canadian state, there’s hope that extra tales and oral histories will come to mild. On this absence, there’s nonetheless house for Two-Spirit and Queer Mi’kmaq to create and recreate new language, tales, and traditions to signify their very own lived experiences and people of their Elders. For instance, in recent times, the Wabanaki Two-Spirit Alliance has provided house for creating “Two-Spirit and Indigenous LGBTQ kin” within the area, together with gatherings just like the annual “Mawita’jik Puoinaq,” and Two-Spirit pleasant cultural experiences just like the “Youth Council Naming Ceremonies.”

Finally, studying colonial information towards the grain can provide perception into Two-Spirit histories in Mi’kma’ki regardless of the numerous absences in supply materials. Nonetheless, we assert that there’s extra energy in creating modern Two-Spirit traditions and language because it displays the historic risk of Queer Mi’kmaq. Whereas this doesn’t negate the necessity for historians and archivists to search out colonial information which may present additional historic context, it does require that these information be learn alongside a Mi’kmaw worldview and, ideally, lived expertise. Our hope is to encourage L’nu’okay youth and students to proceed the research of Two-Spirit and Queer histories and cultures all through each tutorial and cultural pursuits.

Emily Pictou-Roberts is a Two-Spirit member of Millbrook First Nation. She has beforehand been a Mi’kmaw Historical past Interpreter on the Millbrook Cultural and Heritage Centre, and as Atlantic Canada’s First Auntie-in-Residence. At present, Emily is the Indigenous Pupil Assist and Outreach Coordinator on the College of King’s School, the place she advocates for Mi’kmaw views, information, and approaches in help of scholar wellness.

Jess Wilton is a queer historian and doctoral candidate within the division of Historical past at York College. Her analysis focuses on the histories of 2sLGBTQIA+ communities in Atlantic Canada within the late 20th century. She is the visitor editor of the Queering Atlantic Canada sequence on activehistory.ca.

Additional sources

Joseph Randolph Bowers, Mi’kmaq Puoinaq Two Spirit Drugs: Sexuality and Gender Variance, Spirituality and Tradition

Media Co-op, Scott Neigh interview with John R. Sylliboy, “A voice for Two-Spirit individuals in Atlantic Canada”

Wabanaki Two-Spirit Alliance, Two Spirit-Library.

Qwo-Li Driskill, “Doubleweaving two-spirit critiques: Constructing alliances between native and queer research”

Associated