Home keys are prosaic objects that carry extraordinary significance as symbols of residence, safety, place. Suppose for a second: what do your home keys unlock? Do you all the time carry your home keys with you whenever you go away the home, or is your door normally unlocked? Do you, like me, generally verify for the keys in your pocket or your bag to be sure to didn’t overlook them? Have you learnt them by their cool, metallic really feel or are you able to recognise them by sound — their jangle or clink? Have you ever had your home keys for a very long time? Did somebody give them to you in order that you would open the door to the place you name residence?

In 2008, Zulfiye (not her actual identify) advised me about her Crimean Tatar household’s home keys, which her dad and mom handed all the way down to her whereas they lived in exile following Stalin’s mass deportation of Crimean Tatars in 1944. She advised me, ‘These have been the keys of my dad and mom; I carried them again to my homeland with me’. When Zulfiye returned from Uzbekistan in 1991 along with her three younger youngsters, the home keys her dad and mom had stored nonetheless match the locks of her household’s pre-deportation residence. Unable to purchase it again, Zulfiye’s younger household bought a shack in the identical city from which her dad and mom had been deported a technology earlier and slowly constructed it into an acceptable dwelling. The previous keys to the misplaced residence remained within the household — functionally ineffective, however symbolically potent as a reminder of the household’s journey from Crimea to Uzbekistan and again. Zulfiye’s story just isn’t distinctive amongst Crimean Tatars. Some households, given mere minutes to pack for his or her deportation to an unknown vacation spot, took their home keys with them. Was it out of behavior — a reflex at leaving the house — or did they anticipate an eventual return? May the home keys held in exile be something greater than a bitter reminder of the house that was unjustly taken?

From 2008 to 2009, as a part of my ethnographic analysis amongst Crimean Tatar repatriates, I recorded a handful of Crimean Tatar household tales like Zulfiye’s about the home keys they held in exile. Their narratives recommend that home keys turned far more than mere reminders of loss. These mundane objects remodeled into household heirlooms, claims of possession, and materials reminders of what the Crimean Tatar political combat was and is for — even now, many years after they received the suitable to return to Crimea within the final years of the Soviet Union, and even now, as Russian occupation makes an attempt to subdue these Crimean Tatars who’ve remained in Crimea since 2014. Home keys function at present as small armour in opposition to the forgetting induced by navy occupation, pressured removing, and elimination. In exile, they signified a refusal to concede to the lack of a house and a homeland; after return, after the Russian occupation of the Crimean Peninsula in 2014, these home keys symbolize a yet-unfulfilled dream for equal rights and authorized protections in a Crimea free from authoritarian rule. The Crimean Tatar home secret is a aspect of cultural heritage and a reminder of this neighborhood’s respectable wrestle to exist in the identical Crimea from which they have been displaced over centuries of Russian and later Soviet rule.

On this sense the home key turns into endowed with the protecting powers that twentieth-century anthropologists like Franz Boas described in amulets: contextually important objects that defend in opposition to evil. Home keys immediate tales related to the occupied residence. These tales are the noise that may interrupt the regime of silence imposed by way of the gradual violence of settler colonialism. Greater than inert objects, home keys ignite the fuse between an object and the act of remembering; they repel the opportunity of erasure. Tales that start with the cool, metallic reality of keys metonymically stand in for the hope of some form of reparative justice in the long run.

Crimean Tatar tales about home keys haven’t but been comprehensively collected, however moderately exist in scattered archives and in literary depictions of deportation and return. It’s also true that many Crimean Tatars have been displaced from rural properties that might not have used door locks commonly, as Crimean Tatar photographer and researcher Emine Ziyatdin identified to me. But as I returned to my analysis in pursuit of tales about home keys, I began to study different tales, and a small however important sample emerged. Historian Martin-Oleksandr Kisly, who wrote concerning the Crimean Tatar return to Crimea in his 2021 dissertation, remarked on the symbolic which means of home keys in Crimean Tatars’ narratives in a footnote and recounted two girls’s tales. The British author, Lily Hyde, used home keys to inspire the story of a Crimean Tatar woman’s try and get better data about her household’s misplaced Crimean residence in her 2008 novel Dream Land. Some characters within the e book expertise the keys as icons of a thwarted previous or burdens within the current; for the protagonist, the home keys fill in gaps about her household’s pre-deportation life and, most significantly for the story, affirm their troublesome resolution to return. The reminiscences triggered by the home keys persuade the fictional woman that her household’s return is simply.

Palestinian narratives

I advised you earlier that between 2008 and 2009, as a part of my ethnographic analysis amongst Crimean Tatar repatriates, I recorded a handful of Crimean Tatar household tales about the home keys they held in exile. However what I haven’t mentioned but is that I had practically forgotten about these tales. I forgot about them till I entered into lengthy and illuminating dialogues with college students from Palestine who got here into my classroom on the school the place I educate. From them I realized that home keys have lengthy been central to narratives of Palestinian dispossession (a commonality between Crimean Tatars and Palestinians that Kisly additionally famous). Palestinians yearly mark the 1948 Nakba (or ‘Disaster’) that resulted within the flight or expulsion of an estimated 750,000 Palestinians from their properties throughout what Israelis commemorate as their Warfare of Independence. To today, Palestinians’ proper to return stays a but unachieved political objective. Ongoing Israeli settler enlargement in West Financial institution territories continues to threaten the properties and lives of Palestinian residents. On the time of writing, Palestinians in Gaza face ongoing devastation in Israel’s brutal retaliatory marketing campaign in opposition to the Hamas-led assaults of seven October 2023, which has come underneath growing worldwide condemnation.

The anthropologist, Dima Saad, describes the centrality of home keys for Palestinians, as they’ve been ‘mobilized from non-public spheres to public realms — sacralized and charted as symbols of collective loss, thereby binding networks of Palestinians in exile’. Others have documented how the home key recurs in Palestinian artwork practices: from venues just like the Berlin Biennale, to annual poster competitions, to the monumental skeleton key sculpture generally known as the ‘Gate of Return’ that’s put in on the entrance to the West Financial institution Palestinian neighborhood of Aida. To enter Aida by way of the ‘Gate of Return’, one passes by way of a keyhole-shaped construction atop of which is mounted an enormous home key. All of those practices take away the important thing from the context of the familial and home, and place it as a substitute in a public and communal context of loss and hope for return. In Palestine, as in Crimea, the home key turns into an amulet that braces in opposition to the destruction of reminiscence and provokes tales concerning the misplaced residence. These Palestinian tales jogged my memory of what I had as soon as heard from Crimean Tatars and prompted me — a US-based researcher who has not visited Crimea since 2015 — to not overlook the symbolic efficiency of an in any other case mundane object.

What started as a easy commentary about how home keys signify in these disparate narratives of exile is suggestive of one thing which I feel may be greatest characterised as a shared ethos of refusal: the refusal to overlook, the refusal to be narrated out from the triumphant histories written by extra highly effective actors, the refusal to consent to elimination. Settler colonialism, in keeping with the distinguished theorist, Patrick Wolfe, turns into silently infrastructural. It bets in opposition to the displaced and the conquered, assuming they are going to finally overlook concerning the injustice of their occupation and undergo an inexorable ‘logic of elimination’ — both by way of outright extermination or the much less ostentatiously violent practices of coercive assimilation. The home keys held in exile endure as reminders of the continuing pursuit of justice from Crimea to Palestine and past.

Ukrainian dispossession

In territories of Ukraine riven by Russian aggression since 2014, a brand new archive of tales about home keys is taking kind. The previously Kharkiv-based psychologist, Valentyna Pavlenko, just lately wrote about how the full-scale invasion remodeled her keys into objects that ‘now immediate a swarm of reminiscences and feelings… My keys have been beforehand simply an instrument to open the door. Now after I see them in my purse, they symbolize the impossibility of returning residence, of returning to a longed for, dreamed of, peaceable life.’ Private and collective tales about home keys have appeared in a variety of creative contexts. The artist Diana Berg is pictured holding two units of keys in an April 2022 interview about her double displacement from Donetsk to Mariupol to Lviv and the yet-untold horrors of Russian occupation. Home keys function in photographer Alena Grom’s 2017 unfinished mission about fleeing Donetsk titled, merely, Keys. Artist Dima Kozakov exhibited a set of keys left to him by mates fleeing the full-scale invasion in his 2023 set up Home. Keys maintain nice significance for the celebrated author, Olena Stiazhkina. She discloses in a current interview how the 2022 occupation of Mariupol prompted her to lastly take away from her purse the home keys to her Donetsk residence, which she fled in 2014. She determined to deal with them as a substitute as a small artwork set up.

Stiazhkina describes how inserting her Donetsk home keys alongside the keys of others on the door of her Kyiv condominium was ‘a small gesture, an act of solidarity with these individuals whose grief is actually higher than my infantile attachment to the keys’. Diminishing the importance of the keys as private mementos of loss and hoped-for return, Stiazhkina recontextualises them as collective objects that obstinately reject Russian occupation. She follows her story about keys with a press release about her absolute conviction that every one Russian-occupied territories, together with her personal, will probably be returned to Ukrainians. Her Donetsk keys, which she ‘greets every day’, have turn out to be an amulet, preserving her religion that finally justice will probably be served: ‘that these will probably be our cities and that we’ll return there’. In all of those divergent contexts, the home key stands in for the safety of feeling at residence and secure on the earth. As these tales age and get retold, they usually come to symbolise the hope that sooner or later the home keys will assist restore some model of the misplaced residence and rebalance the scales of justice.

Permission to relate

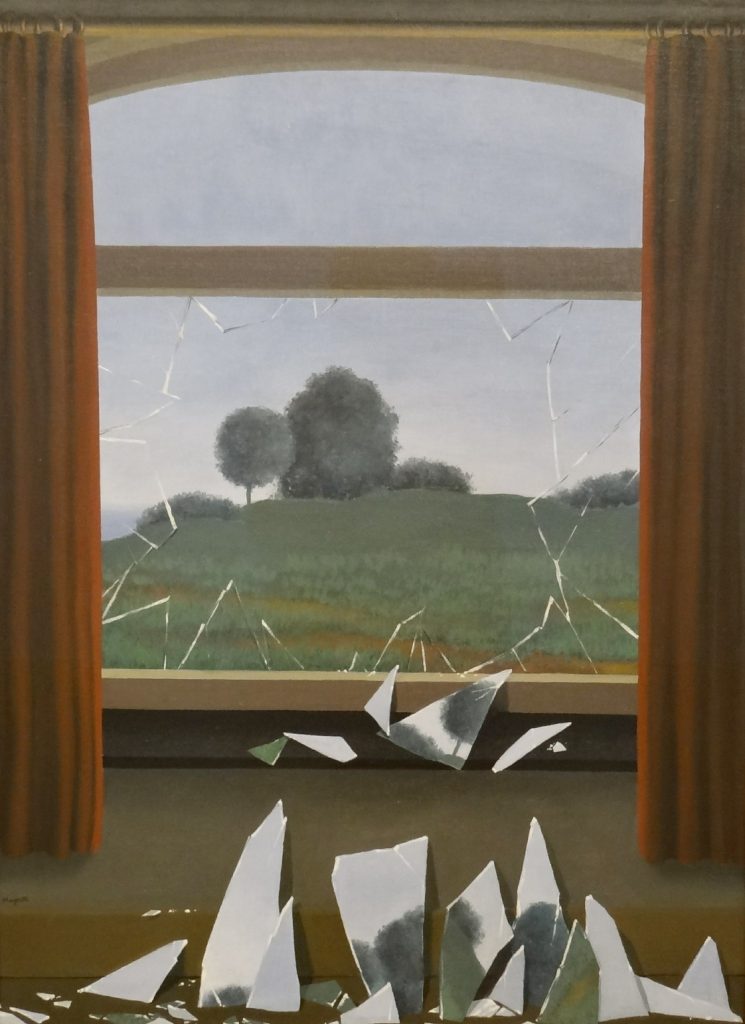

La clef des champs (The important thing to the fields), 1936, Rene Magritte, Museo Thyssen-Bornemisza, Madrid. Photograph by Rex harris by way of Flickr

Throughout a June 2025 public dialog on justice and time held in Lviv, the worldwide lawyer and author, Philippe Sands, spoke about distinct but overlapping classes of justice. Sands argued for types of justice in but additionally past the felony enviornment, the place trials might result in convictions and sentences, however the place outcomes will be elusive or painfully gradual to reach. Sands famous that justice could be very related to storytelling, and subsequently that literature, writing, movies, visible artwork, and music have an enormous half to play in elucidating paths to justice. The amulet in opposition to elimination that’s the home secret is the fabric that precedes the story; it triggers a narrative’s telling and retelling, it forbids us to overlook for lengthy.

Tales might appear to be weak weapons in opposition to the militarised violence of occupation and dispossession. But what Edward Mentioned, talking to the Palestinian context, as soon as described as ‘the permission to relate’ is a central concern that weaves by way of scholarly disciplines from North American Indigenous research to postcolonial principle. Who has the permission to relate their very own story? In up to date Indigenous scholarly and activist circles, storytelling is usually known as ‘storywork’, marking it as a respectable, severe apply. Storywork goals to rebalance the narrative asymmetries and biases handed down by generations of the highly effective, whereas emphasising the varied and artistic methods through which tales are stored alive: to file historical past, cosmology, legislation, reminiscence, expressive practices, kinship networks, and extra. There may be energy within the tales that refuse to be forgotten.

Crimean Tatars, like Palestinians, like Ukrainian residents underneath Russian occupation or navy assault, are individuals who refuse to consent to their very own elimination. They might maintain on to their home keys — to their tales and their songs and their reminiscences — as amulets in opposition to the highly effective tide of forgetting. These amulets maintain the promise of a future secured in opposition to elimination. They harbour a religion in justice. Their resonance throughout time and place prompts us to concentrate, or, as in my case, to recollect the tales with which I had as soon as been entrusted. These amulets ought to inspire us to construct new archives of tales in order that these tales will be retold — in books that will probably be revealed and artworks made, and in struggle crimes tribunals that may sooner or later be held.

As ongoing processes of settler domination increase in Crimea, in Palestine, and within the occupied territories of Ukraine, on a regular basis objects like home keys will accrue ever extra which means and symbolic energy. There are new tales, painful and hopeful ones, being produced now. Let these tales remind us that whilst geopolitical machinations and neoimperial rivalries cleave individuals aside, widespread experiences of dispossession hyperlink individuals collectively. The easy object’s cussed materiality shouldn’t be underestimated; it thwarts and exposes the grinding wheels of settler elimination and its assault on reminiscence. The home key signifies the refusal to be forgotten and the insistence on an eventual flip in direction of justice, right here and there — in 1944, 1948, 2014, 2022, at present, and tomorrow.

This text was first revealed by the London Ukrainian Overview on 2 October 2025. The creator needs to thank Emine Ziyatdin for feedback on an earlier model of this essay. Any omissions or errors are solely the creator’s accountability.