The history of medicine is, for essentially the most half, a history of dubious cures. Some had been even worse than dubious: for examinationple, the ingestion of antimony, which we now know to be a excessively toxic metal. Although it might not occupy an exalted (or, for students in chemistry class, particularly memorable) place on the periodic desk as we speak, antimony does have a goodly lengthy cultural history. Its first recognized use came about in historic Egypt when stibnite, considered one of its mineral types, was floor into the strikingly darkish eyeliner-like cosmetic kohl, which was thought to chase away unhealthy spirits.

Historical Greek civilization recognized antimony much less for its results on the spirit world than on the human one. The Greeks knew full effectively that the stuff was toxic, but in addition stored returning to it as a potential type of medicine.

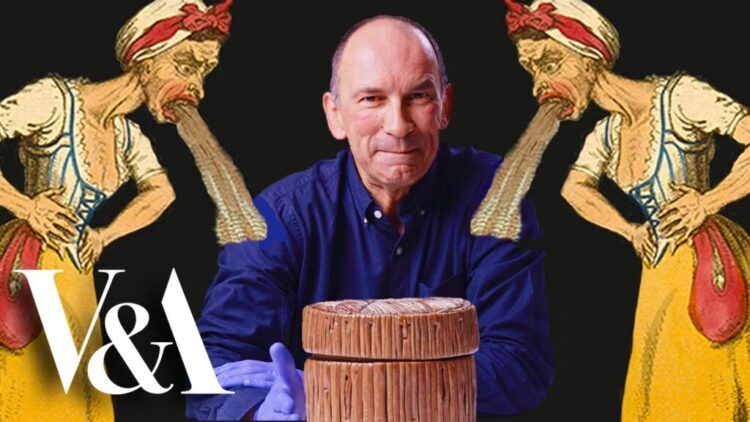

Historical Rome made its personal practical use of antimony, not least in metallurgy, but in addition stored up certain traces of inquiry into its curative properties. As a substance, it was well-placed to capture imaginations extra intensely within the medieval age of alchemy. By the late seventeenth century, people had been drinking wine out of antimony cups, as unboxed in the video from the Victoria and Albert Museum above.

“The purpose of it’s to attempt to make you vomit and have diarrhea and sweat quite a bit,” says Angus Patterson, the V&A’s senior curator of metalwork. Within theory, this could re-balance the “humors” of which medieval medicine conceived of the physique as being composed. Fancy cups just like the one within the video, which was as soon as owned by a lord, weren’t the one antimony objects used for this purpose: the metal was additionally solid into so-called “perpetual tablets,” meant to be swallowed, retrieved from the excrement, then swallowed once more when necessary — for multiple generations, in some cases, as a form of family inheritorloom. “Undecided I’d fancy swallowing a tablet that had been via my grandpa,” Patterson provides, “however wants should when you may have a stomachache in 1750.”

through Aeon

Related content:

The Color that Might Have Killed Napoleon: Scheele’s Inexperienced

Sir Isaac Newton’s Remedy for the Plague: Powdered Toad Vomit Lozenges (1669)

Primarily based in Seoul, Colin Marshall writes and broadcasts on cities, language, and culture. His initiatives embody the Substack newsletter Books on Cities and the e-book The Statemuch less Metropolis: a Stroll via Twenty first-Century Los Angeles. Follow him on the social internetwork formerly often called Twitter at @colinmarshall.